I stumbled across some new information about Benjamin Black’s father, Samuel Black. Samuel was my 4x-great-grandfather. Up until now, the only documentation I had on him (besides family lore) was a record of his marriage to Elinor Howard in 1812.

Actually, the marriage record is pretty interesting because it’s neither a church marriage certificate nor a locally issued certificate or license. It’s a marriage bond. The Legal Genealogist provides an explanation of what that means. The short version is this: in these pre-industrial societies, the community needed assurance that the two people who intended to marry were on the up-and-up, that is, they weren’t bigamists, they weren’t minors, they weren’t siblings, etc. The solution was usually to read “banns” in the church and give the community the opportunity to bring forward any objections. Later, this was shortened to the old-fashioned statement at weddings about “speak now or forever hold your peace” if you know some reason why the couple should not be married.

These concepts worked great if everyone knew the bride and groom. But what if, for example, the groom doesn’t live in the community. How do we know he’s not a bigamist? The solution was to put up a bond. That is, to guarantee that the parties are free to marry, and that a third party would be willing to guarantee a cash payment to the government in the event that it turns out the groom is a bigamist after all. Because if that should happen, the government incurs a lot of expenses: a judge would have to sort out the dissolution or annulment of the marriage, and there may be children and assets to be sorted out.

You can’t put up the bond yourself, you have to have some third party vouch for you. In Samuel’s case, it was his soon-to-be father-in-law who helped put up the bond. Here is the text1:

Know all men by these presents that we Samuel Black and Benjamin Howard are held and firmly bound unto the commonwealth of Kentucky to the sum 50 pounds current money to which payment well and truly to be made to the said commonwealth we bind ourselves our heirs executors or administrators firmly by these present seated and dated this 13 day of October 1812.

The condition of the above obligation is such that whereas there is a marriage shortly intended to be and and solemnized between the above bound Black and Elenor Howard both of the County of Madison. If there be no lawful cause to obstruct the same then this obligation to be void else to remain in full force and virtue.

In modern times, the act of securing a marriage license takes care of all this business. Who knew?

Anyway. That was the one and only piece of documentary evidence I had about Samuel Black. But yesterday I finally came across his probate papers.

It appears that Samuel died intestate, because the probate records are all about dividing up his land. His widow, Elinor (now going by “Ellen”) automatically got 1/3rd of his property, no questions asked. This is the effect of “dower laws” that were common in this era. The remaining 2/3rds had to be equally distributed to Samuel’s children. Lucky for us this went to probate, because the court had to individually identify all of Samuel’s heirs.

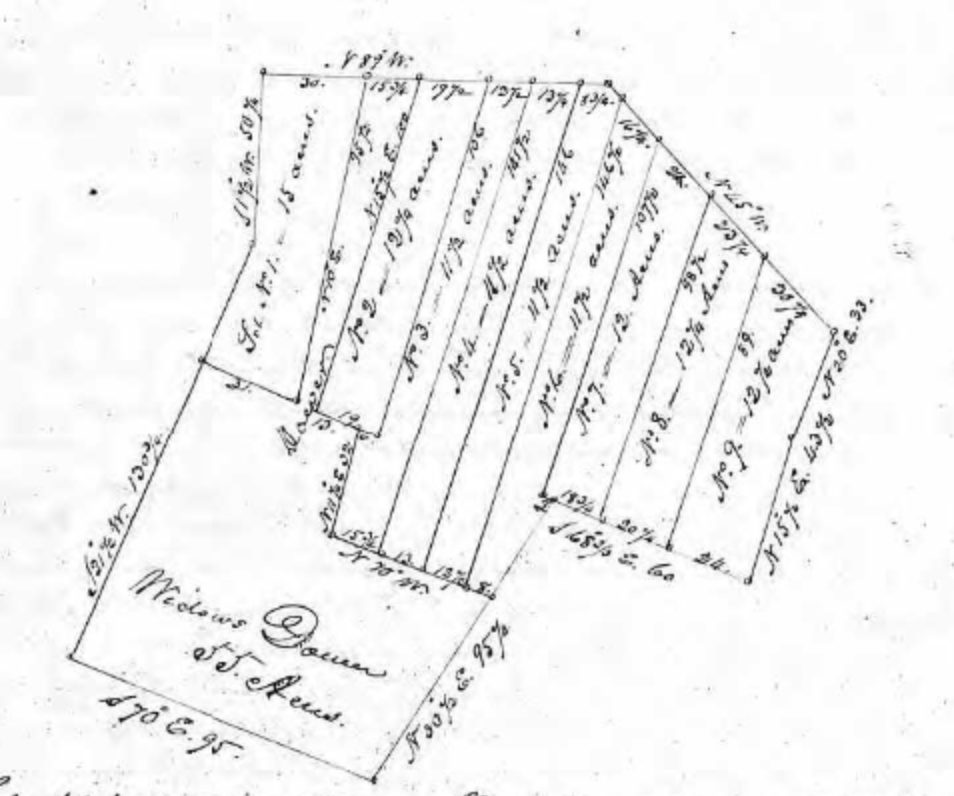

Much of the probate record is about the survey that was done of Samuel’s property, and how the persons commissioned to do the survey also had to decide how to divide things up.

Here’s the text of the probate record2; I’ve left out all the legal descriptions. Note the list of Samuel’s children; it matches my list exactly! I love validation!

In obedience to an order of the Boone County Court made at the February Term 1847 appointing us commissioners to make partition of all the real estate of Samuel Black deceased amongst his children and heirs, we the undersigned James Rice, James Marshall and Moses S. Rice. We proceeded upon the premises of the said deceased on the 5th of Feb. 1847 and were sworn by James Cordiers Esq. to perform the duty required by said order impartially without favor or affection to the best of our skill and judgment. We proceeded first to ascertain by survey the quantity of land in possession fo the dec’d at the time of his death which we found to be 165 acres. We then after laying off dower of 55 acres for the widow of said dec’d out of the said 165 acres proceeded to make partition of the remaining 110 acres into the nine following described lots to wit:

Having thus made the divisions as aforesaid and believing them to be of equal value we proceeded by ballot to assign to each heir his or her particular lot which resulted as follows:

Enoch White and wife obtained Lot No. 9 [Dulcinea]

Boggess and wife – Lot 1 [Catherine]

Grubbs and wife – Lot 6 [Elizabeth]

Margaret Black – Lot 4

Joseph Black – Lot 7

Benjamin Black – Lot 8

Mary Black – Lot 5

Isabella Black3 – Lot 2

Emily Black3 – Lot 3All of which is respectfully reported to the Boone County Court given under our hands this 8th day of February 1847.

James Marshall

James Rice

M.L. Rice

The italicized names are my assumptions about which daughters go with which sons-in-law. We’ve met Catherine Boggess before – if you recall, Benjamin Black’s widow Cynthia (Jones) testified that Benjamin went to live with Catherine and Harrison Boggess when he was 19 years old.

The timing of his father’s probate and Benjamin’s subsequent inheritance is pretty interesting. Samuel would have died sometime in 1846 or perhaps earlier; the land was divided in February 1847. So Benjamin came into inheritance sometime in 1847. This was the same year that he made his abortive attempt to enlist in the Army. By 1849, he was married to Louisa Matthews.

Any guesses as to what he did with his inheritance? The evidence seems to confirm that he sold it as soon he could (I would have guessed this, knowing what I do about Benjamin!). A deed index covering the period 1846-1852 shows that Benjamin sold his lot to James Marshall4 – probably the same James Marshall who was one of the guys that surveyed the lots on behalf of the court. (The index doesn’t have any dates, I’d have to look it up on microfilm or in a courthouse to confirm the timeline.)

My guess is that Benjamin returned to Indiana with a bunch of cash in his pocket and thus was in a good position to woo and marry his bride Louisa. I’m not sure that he was a very good steward of his father’s legacy (although the proceeds from selling 12 acres may not have amounted to much). As Benjamin and Louisa’s family grew, they moved from rented farm to rented farm and within a few years the family would be nearly destitute and dependent on Louisa’s father to support them in North English, Iowa.

Next time, more about Samuel’s father-in-law (Benjamin’s maternal grandfather and namesake) Benjamin Howard.

1Ancestry.com. Kentucky, County Marriage Records, 1783-1965 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016. (Image 700 of 752)

2Ancestry.com. Kentucky, Wills and Probate Records, 1774-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: Kentucky County, District and Probate Courts. (Image 49 of 485).

3Isabella and Mary were minors at the time of their father’s death, and a guardian was appointed to look after their interests. I believe that in this context, guardianship only extends to their financial assets. See Guardian and administrator bonds, 1820-1856, Kentucky County Court (Boone County); Guardian Bond (Image 326 of 839)

4Deeds, 1799-1912, Boone County (Kentucky). Clerk of the County Court. Digital images on FamilySearch.org (Image 49 of 660)

Another WOW, Karen. I can’t comprehend all of the info!!! Good job!