It is so fun to research family history at a time when records are readily available on the internet. I found some truly fascinating information about Salathiel’s doctor and the politics of his home town prior to, during, and after the war. This is a rather long post and takes a big detour into the politics of the time, but it is really quite interesting how Salathiel’s pension application was nearly derailed by partisan politics!

As we saw last time, Salathiel got very ill during the fall of 1864, and he claimed it was during this time that his Rheumatism became debilitating. He left the Regiment and was sent not to a field hospital but to one of the big military hospitals in Nashville. From his original affidavit:

He was treated in hospitals for his Rheumatism as follows: at first for about a month commencing about September 1864 in General Hospital No. 15 at Nashville, Tennessee in charge of Dr. W. M. Chambers…

Salathiel’s pension file includes an affidavit signed by Dr. Chambers himself. Here’s what Chambers had to say about his treatment of Salathiel before and after the war:

…He [Chambers] was acquainted with said soldier for more than one year next before said soldier entered to said service.

He further says that he saw said soldier immediately when his return from the army upon his discharge therefrom, that he was then suffering from Rheumatism in his shoulders and limbs, and that he treated him for it at that time and occasionally so long as he had any personal knowledge of said soldier’s physical condition which continued up to about September 1880…

…Had not regained his normal health when he last saw said soldier about September 1880.

(I wonder if it was by chance that Salathiel got sent to Dr. Chambers’ hospital in Nashville, or if maybe his commanding officers sent him somewhere where they knew he would get care from a home-town doctor?)

It was the duty of the Pension Board to fully verify all of the claims made by a soldier in his application for a pension. The Pension Board first sent an inquiry to the Surgeon General to confirm whether Dr. Chambers was really at General Hospital No. 15 in Nashville. The U.S. Army Surgeon General replied that yes indeed, Dr. Chambers was the Surgeon in Charge of that hospital in the fall of 1864.

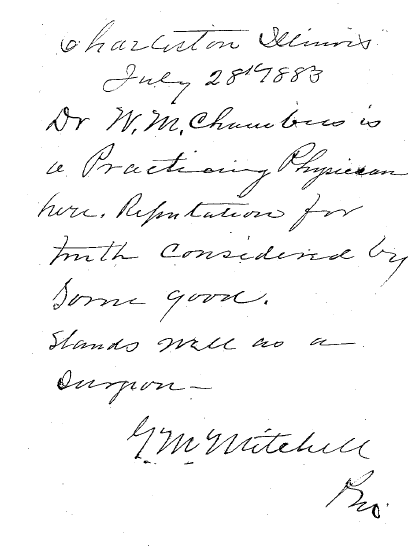

Next, the Pension Board sent an inquiry to the Sheriff of Coles County to inquire “as to the standing in the community and the general reputation for truth” of W.M. Chambers, M.D. Was it normal practice to send such an inquiry? I’m guessing it probably was (the inquiry was on a form letter), but here is the response that was received:

Dr. W.M. Chambers is a Practicing Physician here. Reputation for truth considered by some good. Stands well as a surgeon. G. M. Mitchell

Talk about “damning with faint praise” – perhaps the language of the late 1800’s stands as a barrier here, but to state that Dr. Chambers’ reputation for truth was considered by some to be good hardly sounds like a ringing endorsement. Who is this Mitchell person, and does he have something against Dr. Chambers?

Well it is quite amazing what you can find on the internet: Sheriff Mitchell and Dr. Chambers were probably on less than friendly terms.

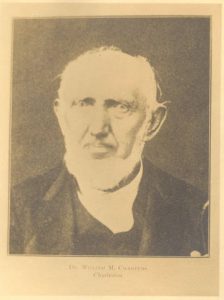

Dr. William M. Chambers was a respected member of the community and is included in a book of biographical portraits of notable Coles County citizens. A bit of ‘googling’ for Dr. Chambers also turns up a very interesting book, “Abraham Lincoln and Coles County, Illinois” by Charles H. Coleman.

It turns out that Abraham Lincoln had some very tight connections to Coles County. His father and step-mother moved there in 1831, right at about the time the future President was striking out on his own as a young lawyer. Charleston, the County Seat, was the scene of the fourth of the seven famous Lincoln-Douglas debates. As you might recall, Lincoln and Douglas were vying for a Senate seat and at that time, Senators were elected by legislatures, not by popular vote.

In the years before the Civil War, the political parties were very different from what we know now. Generally speaking, the Republicans were more popular in the north and opposed slavery and secession while the Democrats were more popular in the south and were sympathetic to a “states rights” position on slavery. But there were other political parties trying to occupy the middle ground. The Whig Party was dying out, with many of its former members in the North becoming Republicans. In the South, former Whigs were attracted to the “American Party” – also known as the Know-Nothing movement. The Know-Nothings were extremely anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant, and they tried to find a middle ground with respect to slavery. The Know-Nothings tried to re-elect former President Millard Fillmore (the last of the Whig Presidents) as their candidate in the 1856 election, but Fillmore came in third behind Democrat James Buchanan and Republican John Fremont.

When Lincoln was running for Senate in 1858, he needed to gain the support of “Fillmore Men”. By 1858, there were really only two political parties, Republican and Democrat, and the former supporters of Fillmore were up for grabs. Dr. Chambers was one of the more prominent Fillmore Men in Coles County, and Lincoln’s Republican supporters there were anxious that he come over to Lincoln’s side. Lincoln and Chambers actually exchanged letters (!), and eventually Chambers chose to side with the Republicans. In fact, it was Dr. Chambers himself who introduced Lincoln to the audience during the Lincoln-Douglas debate held in Charleston!

As the war broke out, Dr. Chambers was active in organizing recruits and enlisted himself as a brigade surgeon in the Union Army. He served with distinction and according to his biography, introduced some innovations related to the treatment and care of soldiers.

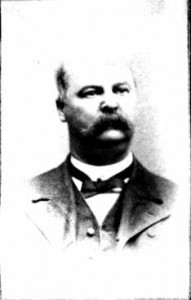

Meanwhile, Greenville M. Mitchell was also a prominent member of the community. He was younger than Dr. Chambers – in fact, he was born the same year as our Salathiel. Mitchell enlisted in the 54th Illinois Infantry and rose to the rank of Colonel. In March of 1864, Mitchell and many of his men were on leave and had came home to a very tense situation.

Although Illinois was a Union state, the war was not all that popular, and many people were outspoken in their opposition. And remember that there were still lots of Democrats in the North! Some of the people opposing the war seemed to take things too far, appearing to be traitors to the Union cause. They were called “Copperheads”, a reference to being “snakes in the grass” since they were sometimes coy about their opposition. Copperheads often sent letters to their friends serving in the Army, encouraging them to desert. This was upsetting to many soldiers – the “Morning to Midnight” book contains a great deal of detail about what loyal soldiers thought about Copperheads and the other opposition movements back home.

So while Col. Mitchell and his men are in Charleston on leave, they get word that a Coles County judge had supposedly allowed four Union deserters to go free. They decided they would confront the judge about this and force him to swear an oath of allegiance. Some local Copperheads, led by the Coles County Sheriff John O’Hair, got wind of this and were determined to confront the soldiers. Apparently everyone had been drinking and things escalated into what is now known as the Charleston Riot. In the end, nine men were killed and a dozen were wounded. Col. Mitchell himself was wounded, and a potentially fatal shot was said to have been stopped by his pocket watch. Bringing the perpetrators to justice was a long drawn-out affair, and still fifteen years later there was bitterness and anger about the whole incident. (The 150th Anniversary of the Charleston Riot was observed just this year – read more about it here and here.)

At the end of the war, Col. Mitchell was elected Sheriff of Coles County, filling the office that had been held by Copperhead John O’Hair during the war.

And as for Dr. Chambers, whatever would have caused Sheriff Mitchell to side against him? The final clue is in the last paragraph of his biographical sketch – “The Doctor is a staunch supporter of the Democratic Party…”

I picture Mitchell as truly loyal to the Union and Republican cause. He took a bullet during the riot, defending his men against Copperhead traitors. Dr. Chambers acted the part of a Union loyalist during the war and probably bragged about his close association and correspondence with President Lincoln. He soon changes his stripes, though, and the former Whig/Know-Nothing doctor quickly signed onto the Democratic Party once the war was over. It probably made Mitchell’s stomach churn.

So it’s perhaps no surprise that when Salathiel’s pension paperwork comes across his desk, Mitchell writes what he can to help the cause of a fellow soldier, but cannot bring himself to actually put in a good word for Dr. Chambers.

Salathiel’s pension was ultimately approved, but he’s lucky that Sheriff Mitchell kept his comments civil!

____

Finally, I must pass along a wonderful anecdote from the Coleman book about Lincoln that includes our Dr. Chambers. If you liked the portrayal of Lincoln by Daniel-Day Lewis in the Speilberg’s “Lincoln”, it will be easy for you to picture this little episode.

After Lincoln had been elected President but before he took office, he came to Coles County to visit his step-mother. Of course everyone would have been excited about this, and the important citizens of the County were anxious to get invitations to any social event that the President-Elect might attend. Dr. Chambers was one of those citizens who got such an invitation. According to Coleman,

After Lincoln had been elected President but before he took office, he came to Coles County to visit his step-mother. Of course everyone would have been excited about this, and the important citizens of the County were anxious to get invitations to any social event that the President-Elect might attend. Dr. Chambers was one of those citizens who got such an invitation. According to Coleman,

Dr. W.M. Chambers was one of those present to greet the President-elect. He said to Lincoln that he had a message for him from a mutual friend, Pete Miller. Miller, a Democrat, had asked Chambers to tell Lincoln that, although he had not voted for him, he believed that Lincoln had been lawfully elected; and that, if anybody attempted to prevent his inauguration on March 4, he “would shed the last drop of his blood” in support of Lincoln’s claim. With a twinkle in his eye, Lincoln replied to Chambers:

‘Perhaps he would be like the young man who was going to war, whose two loving and admiring sisters had made an embroidered belt for him to wear, and when they had it completed, they asked him what motto they should put upon it, “Victory or death?” “No, no,” says he, “don’t put it quite that strong. Put it “Victory or get hurt pretty bad,”‘

I picture Dr. Chambers laughing nervously at this story; I think Lincoln saw right through him!