My great-great-grandparents Gustaf and Clara met and were married while they were servants at the Nobynäs estate in the 1850’s. Shortly after they were married, they left Nobynäs and eventually acquired a farm of their own. Twenty years later, their future son-in-law, Gust Rudeen (my great-grandfather) worked at Nobynäs for one year as a coachman (I just found that out last week). Throughout this period, the Nobynäs estate was owned by the Stierngranat family.

We visited Nobynäs during our trip to Sweden in 2013. It has been partially converted to a bed and breakfast and we stayed there three nights. During our stay, we learned something of the colorful history of Nobynäs and about one of the more eccentric members of the Stierngranat family. Since then, I’ve done a bit more digging and have been thoroughly entertained by what I have found. I have enough material here to span across several postings, but since the relationship to our family is really only tangential, I’ve condensed everything into this single, long post. So pull up a chair and a cup of coffee and prepare to have your mind blown.

The Stierngranat Noble Family

Starting in the Middle Ages (1000-1300 A.D.), the King of Sweden recruited military officers and cavalrymen from the wealthy classes by granting noble titles and tax exemptions (he couldn’t afford to pay cash). Over the years this practice evolved to offer different benefits, but the system of granting noble status continues to this day. Of course today Sweden is a modern democratic society, so nowadays the whole process is mostly ceremonial. When noble status is granted, a record is made at the Ridderhuset (House of Nobility) and each entry is assigned a unique number. The lower your number, the more ancient your family’s claim to noble status. I should note here that the Eket farm where the Rudeen family lived for several generations was owned by the Bonde noble family, which is number 11 out of 2,352 on the list. We also saw in the nearby Marbäck church a memorial to the Pistol noble family, number 253 on the list.

The Stierngranat family did not come by their noble status until later, so they are relative newcomers at number 1506. Their first nobleman was Olof Hjerpe Stierngranat and he was knighted on August 21, 1716. When you get knighted, you get to have a coat of arms and it seems (as we saw with the Pistol family) that you usually take on a new name that can be represented graphically on your coat of arms. I thought the Pistol coat of arms was pretty silly, but I think the Stierngranat family is sillier yet. “Stierngranat” is a melding of two words, stjärna (or “star”) and granat (a shell or grenade, related to the word “grenadier”). So of course the Stierngranat coat of arms has some stars and an exploding grenade. I’m not even kidding, have a look at it at right.

Olof’s great-great-grandson Gustaf Georg Henrik Stierngranat married Antoinetta Ulrika Augusta von Liewen (from another noble family at number 43 on the list!). It was the von Liewen family who had purchased Nobynäs in 1829.

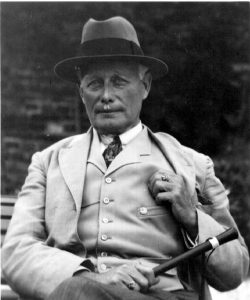

Gustaf Geroge was probably lord of the manor while my ancestors Gustaf and Clara worked there. The next heir, George Gustaf’s son Malte Gustaf Henrik (the senior Malte, shown at left), would have been 12 years old at the time of Gustaf’s and Clara’s marriage.

Malte Gustaf Henrik eventually became a “chamberlain” to the King of Sweden, a mostly ceremonial title but he would have gone to Stockholm on a regular basis for important state occasions. In 1870, Malte Gustaf Henrik married a woman from Stockholm and brought her back to Nobynäs. A year later their son Georg Malte Gustaf August Liewen Stierngranat was born. For most of his life, the junior Malte went by Malte Liewen Stierngranat and from here on I shall refer to him as simply Malte. He led a remarkable life with improbable encounters with many historical figures, reminding me of Sweden’s answer to Forrest Gump.

When my great-grandfather Gust Rudeen worked as a coachman at Nobynäs in 1881, Malte would have been 10 years old. No doubt Gust helped transport young Malte and the rest of the Stierngranat family in their travels in and around the Lake Ralången area.

A year later, Gust and his bride-to-be Augusta (daughter of the former Nobynäs servants Gustaf and Clara) left for America. I wonder, did they happen to read of Malte’s exploits some 17 years later when he made headlines in newspapers all across the United States?

1898 – Malte Leaves for America

As a young boy, Malte had only a grammar-school education that he had gained in the nearby city of Linköping. During his teenage and young adult years, he lived a life of privilege but his parents tended to spend more than they earned from the cash rents on the Nobynäs estate farms. They sometimes had to sell off parcels of land in order to make ends meet. Gustaf and Clara themselves bought their Skallycke farm from the Stierngranat family sometime between 1876 and 1880. At one point, the Stierngranats supplemented their income by renting out the bottom floor of the Nobynäs manor to be used as a ladies’ school. But they continued to have lavish parties in Stockholm and at their country villa, Sigridsborg, near Frinnaryd. There are apt comparisons to the Downton Abbey TV series, for sure!

When we stayed at Nobynäs last year, the owner told us the tale that Malte wanted to travel to America as a young man but lacked the cash to do so. So in the spring of 1898 he visited each of the Nobynäs tenant farms to personally collect the rent payments for the year from each of the farmers. With cash in his pocket, he set off for America. His stated goal was to marry rich. According to his biography, he said,

I will go to America and get hold of a rich lady, it does not matter what she looks like, well it does not matter if the nose sits in the neck.

1899 – Malte Screws Up Bad

Malte had been in America only a few months before his scheme went horribly, horribly wrong. Seems he met a young woman by the unfortunate name of “Lesbia Boswick” and a whirlwind courtship ensued, or at least that’s what Lesbia thought it was. Malte was about to duck out on the whole thing by retreating back home to Sweden, but Lesbia got wind of it and had him arrested for breach of a marriage promise.She sued him for $50,000 in damages. Bail was set at $500. By then, Malte had spent the money he had pilfered from the tenant farmers back home, so off to jail he went.

The matter was taken up by a jury who were mostly unsympathetic to Lesbia and her gold-digging ways. Nevertheless, they found in her favor and ordered Malte to pay damages – not the $50,000 she had asked, but instead just $45.86, a figure arrived at by taking the average of all the jurors’ estimates of damages. Without even $46 to his name, Malte sat in the Ludlow Street Jail in New York City for weeks on end. Finally Malte’s younger brother Gustaf (known as Gösta) set out for America to see if he could rescue Malte.

As is so often the case in European tales, both true and fictional, our hero is rescued by an unexpected inhereritance. An uncle to the Stierngranat brothers, Claes Louis Ferdinand Stierngranat, died on July 7, 1899 and he left $230,000 to be divided equally between his two nephews Malte and Gösta.

Malte appealed to Lesbia to retract the charges, claiming that his Aunt back in Sweden would withhold his inheritance without such a letter. Lesbia refused, and Malte continued to linger in jail, neglecting his appearance and appearing at times to be demented. Friends offered to pay the damages but he refused their offers of help. Newspapers across the country picked up the story. (Though it wasn’t front-page news, I found the story in various newspapers from coast to coast.) Theater managers began dropping by to try and buy the rights to his story, to be produced as a Broadway play (I have not found any evidence that this ever came to fruition).

Meanwhile, his brother Gösta got tired of waiting around. He had become somewhat of a celebrity-by-association and was wined and dined across New York City. His attention drifted away from his brother’s troubles and he soon found himself married to an American woman, Miss M.A. Brown of Philadelphia. Finally, Malte’s attorney Fischer Hansen personally paid the debt, knowing that the inheritance funds were forthcoming. Of course, Malte then tried to stiff his attorney for legal fees and somehow succeeded in doing so by accidentally taking advantage of a legal loophole. The matter went all the way to the New York Supreme Court where the appeal court’s ruling was overturned in 1901 and the case was decided in the attorney’s favor. I don’t know if Mr. Hansen was able to collect his fees.

Because by now Malte had left New York and moved on to bigger and better things.

Malte the Engineer. Or is it Malte the Artist?

Somehow, Malte was able to buy himself some credentials as an engineer. At various times in his life, he claimed to be both a mechanical and a civil engineer. He ended up in Indianapolis, Indiana building the city’s waterworks.

Oh, so humble. Oh, so PHONY – his title at home was a mere “Sir”, not a “Count”. And he abhors newspaper reporters? Yeah, I bet so after his New York experience four years’ prior!

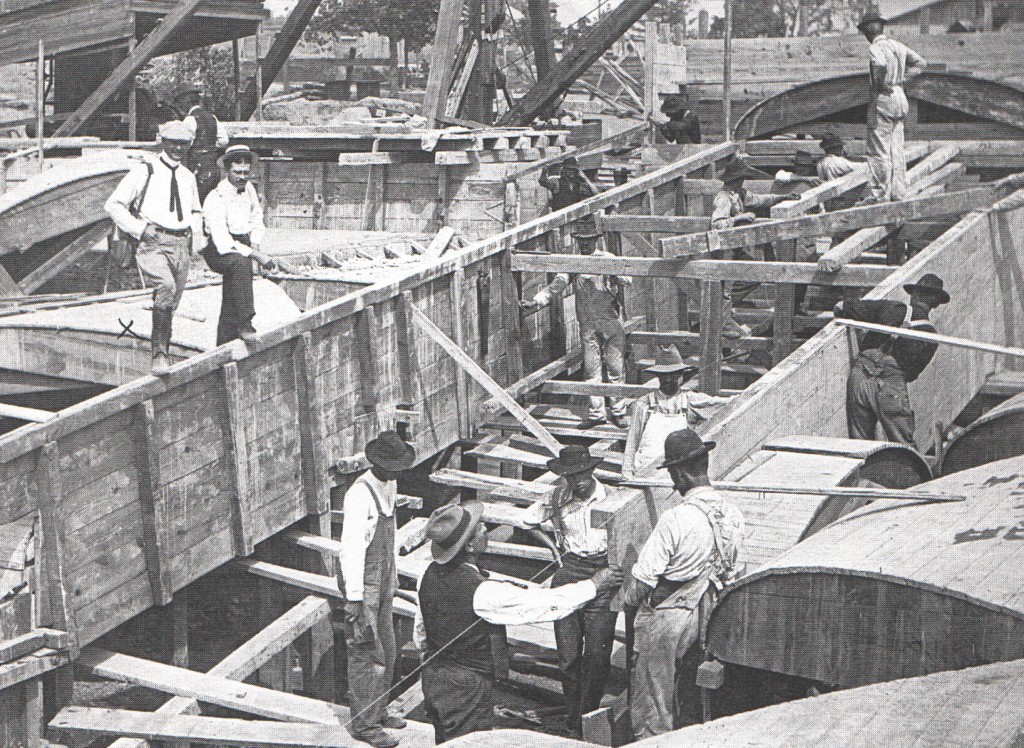

That same year, he worked on a similar project for the waterworks in Washington, D.C. Here he is at far left overseeing the work in his capacity as Project Manager.

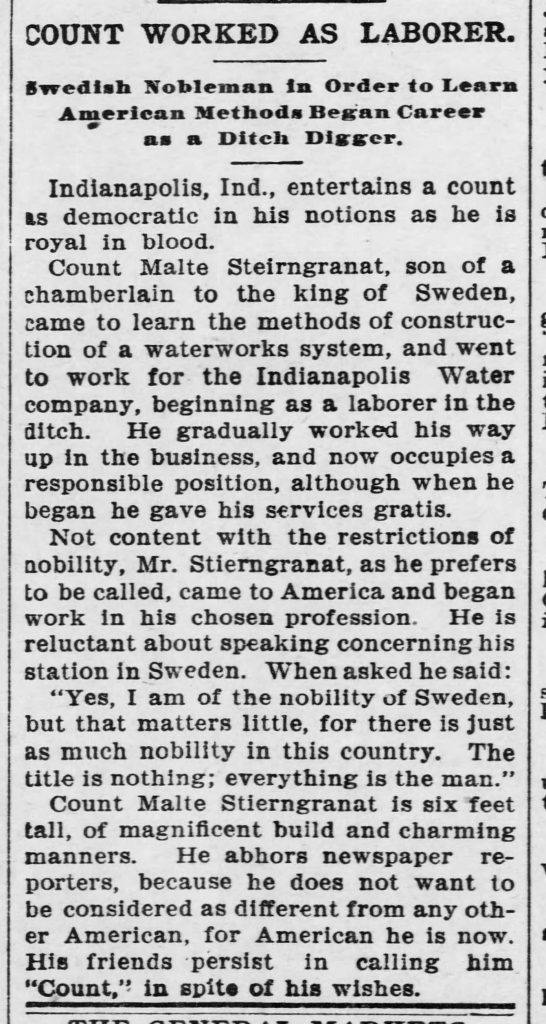

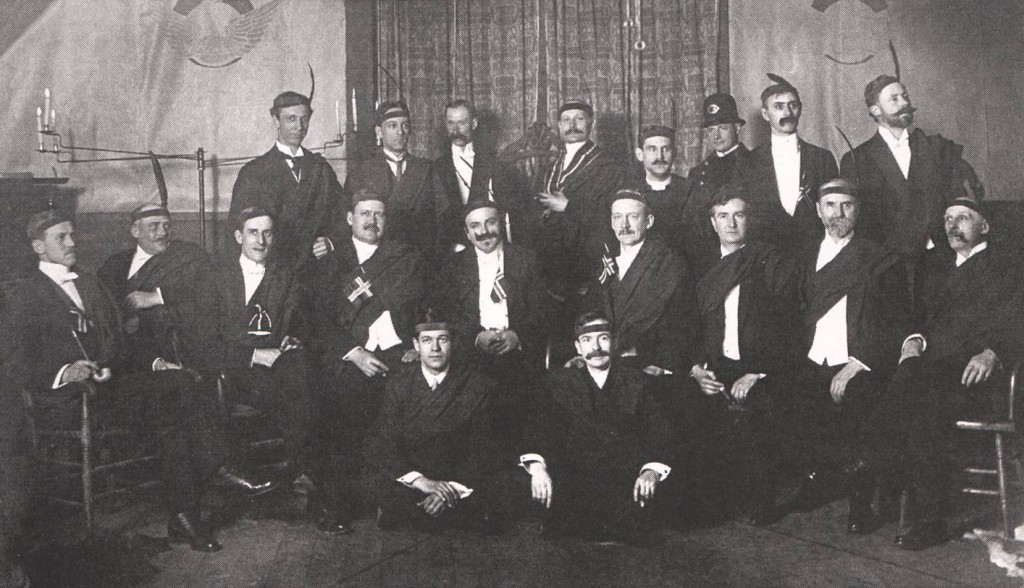

He had also taken an interest in art, paintings especially, and managed to have one of his own works entered at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. His interest in art grew over time and he took special note of the great European works on display in American museums. He was distressed, however, to see so many of them in shabby condition. He decided to pass himself off as a restoration expert. His first restoration attempt ended badly and his restoration work ended up destroying the painting he was trying to save. Somehow, though, he acquired the knowledge and training to become some sort of actual expert. Here he is in 1907 working on a painting by Peter Paul Rubens in the Detroit Museum of Art.

And here I’ve superimposed on the old photo what the painting looks like today:

He eventually tired of his supposed engineering profession. His art restoration work took him to the upper Midwest. He settled in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and was soon taken with Anna Marie Vietor Dahlman. She was the daughter of Senator Anthony Dahlman, a wealthy real estate magnate. They married in November, 1905. No doubt Malte had by then burned through his Uncle’s inheritance, and his wealthy young wife provided the means for him to continue tinkering around with his art hobbies. He promised her an eventual move back to his “castle” in Sweden.

Meanwhile, Malte began hob-nobbing with various members of Milwaukee’s upper crust. His next-door neighbor was none other than the recently retired General Arthur MacArthur. General MacArthur coined the phrase “On, Wisconsin” and was the father of General Douglas MacArthur of World War II fame. MacArthur was great pals with President Theodore Roosevelt, and he invited Malte to join him in visits to the White House. Roosevelt was quite taken with Malte, who now had inflated himself to the title of “Baron” and claimed to be a descendant of Sweden’s most famous monarch, King Vasa. Roosevelt presented Malte with a silver-clad walking cane that Malte carried with him throughout his life.

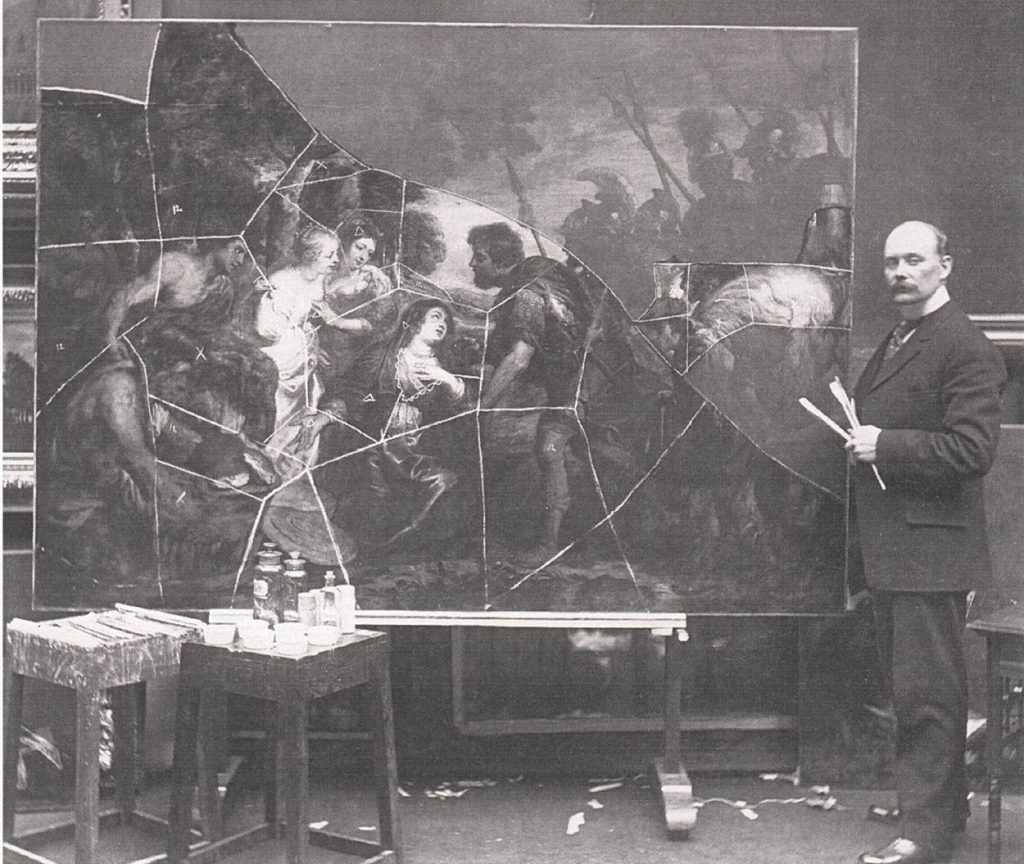

Other celebrities passing through Wisconsin and palling around with Malte included future President Herbert Hoover, polar explorer Roald Amundsen and retired General Charles King. President Roosevelt dropped in from time to time and was once a special guest of the Scandinavian Club that Malte founded in Milwaukee.

In 1908, Malte and his wife Marie set off for Europe on the ship RMS Caronia. They were traveling with the “Lodge of Artists”, a wealthy group of art patrons from Milwaukee. One evening on board ship, the club sponsored a dinner followed by entertainment and an art auction, with Guglielmo Marconi (you know, the guy that invented the radio) being the successful bidder on some of the art works. And I guess I must mention that the ship they were on, the Caronia, went on to some fame of its own. It was in the North Atlantic on April 14, 1912 and sent the first ice warning to RMS Titanic using, of course, Marconi’s own invention to do so. Malte and Marie traveled the world, visiting Africa, South America and Australia. Malte continued accepting commissions to restore artwork, even working on a Rembrandt at one point.

Tired yet? Better grab another cup of coffee. We’ve still got quite a ways to go.

1910 – Malte returns to Sweden

Finally in 1910, Malte and Marie make the move back home to Sweden with their new baby daughter Ulrika. Oh how excited Marie must have been to finally set foot in the grand family manor that Malte had been bragging on all these years! Just one teeny little problem. Remember the rent money that Malte pilfered all those years ago? That was part of a downward spiral for old Chamberlain Stierngranat. He’d been forced to sell Nobynäs back in 1903. Marie was horrified to learn that not only was her husband neither a “Count” nor a “Baron”, he had no castle or manor at all, and the family’s wealth was gone. For the remainder of their marriage, Malte and Marie relied on funds from Marie’s father to finance their lavish lifestyle.

But fund it he did. They settled in Stockholm. Malte used Marie’s money to buy back a small parcel of land from the Nobynäs estate. Here Malte undertook the construction of a grand new manor, to be called Stjärneborg – “Castle of the Stars”. Malte and Marie also welcomed a new addition to the family, a son Rutger.

While his new little mansion was under construction, Malte was delighted to learn that Fifth Olympiad was to be held in Stockholm in the summer of 1912.

As someone with significant American connections, he was of course recruited to be among the organizers for the event. He was named to be one of the “hosts” for the American athletes. He was to help greet the athletes as they arrived in the country, help provide for their accommodations and to generally show them a good time while they stayed in Stockholm.

For his efforts, he was rewarded with the honor of leading the American team into the stadium for the opening ceremonies. That’s Malte, with his hat at his chest, walking behind the guys carrying the “United States” sign. Marie is in the stands, wearing a white coat and hat. She appears to be using a camera to take his picture during his moment of glory.

Malte’s Later Years

Malte got even more eccentric the years that followed. He became obsessed with his own death. Inspired by a visit to the Gaza pyramids of Egypt, he commissioned the construction of a burial pyramid near his Stjärneborg property with the intention that he and his family would be interred there. He also had an oak coffin constructed and he brought it with him on all his travels, just in case he should expire while on the road.

For his own convenience, he built a small railroad station near Stjärneborg. Unfortunately, he failed to clear this with the railroad company in advance and he had to resort to standing on the tracks, waving President Roosevelt’s silver-clad cane at the engineers in order to get the train to stop. Eventually, he got the railroad to recognize the Stjärneborg station and regular stops were scheduled. He fancied himself an architect and designed and built a concert hall in the nearby town of Aneby. The critics had a heyday with it, calling it “cross between a Greek temple and a Swedish factory row house”.

Eventually, things start to unravel for Marie. The last straw was when Malte got one of the servant girls pregnant. She filed for divorce in 1928. She received the Stjärneborg property since, after all, it was her father’s money that had bought and paid for everything. Malte settled elsewhere and remarried, naturally finding a woman of wealth so as to minimize any disruptions to his lifestyle.

Marie died in 1936 and the Stjärneborg property was returned to Malte. He saw to it that Marie was buried inside the little pyramid. Malte began spending his second wife’s money on a renovation of Stjärneborg. She finally got fed up too, divorcing him in 1945.

Malte himself lived for several more years, continuing in his eccentric ways and alternating between his beloved Stjärneborg and Stockholm. He eventually died in Stockholm in 1960 at the age of 88.

His wishes were honored and he too is buried at the pyramid near Stjärneborg alongside his first wife Marie. He instructed that his beloved Roosevelt cane remain with him in the pyramid.

His daughter married but did not have any children of her own, and Rutger his son did not marry at all. His illegitimate daughter (from the fling with the maid) is still living today in nearby Eksjö.

Vandals broke into the pyramid in the 1970’s and stole the precious cane. It is said to have turned up a few years later at an auction in the Russian town of Tula. This may be more legend than truth, and I have not found any credible report about where the cane is now located.

Oh but our story is not done yet. Malte lives on in a most unlikely setting!

Malte’s Legacy Lives On!

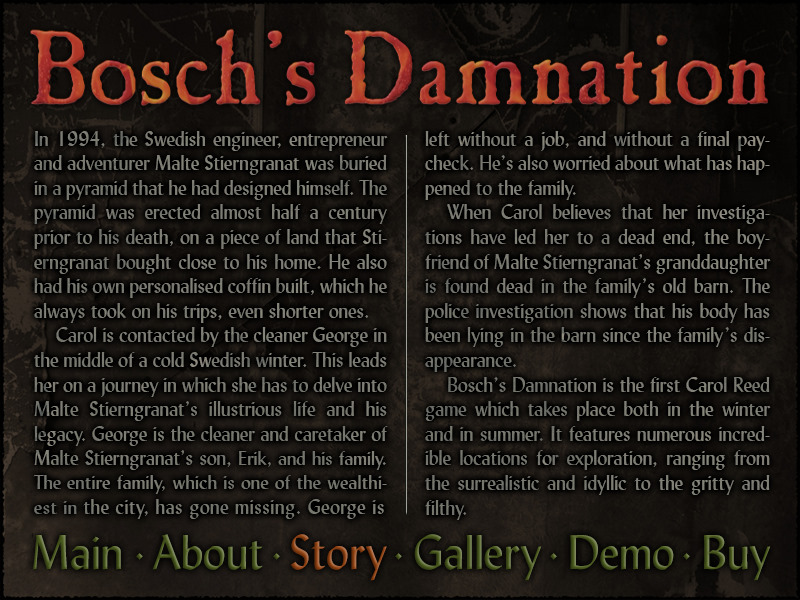

A video game designer has made Malte the subject of a fantasy computer game known as “Bosch’s Damnation”. It is a somewhat fictionalized version of Malte with dates and details modified to suit a more fantastic plot (hah, as if his real life wasn’t fantastic enough!). Here’s the ad for it, and I”m sure you’ll recognize some of the basic plot elements:

Here’s the video “trailer” for the game – you’ll recongize one of the settings, I’m sure.

There are other videos available on YouTube, some of them showing in more detail the puzzle elements included in the game. Right now, the computer game is in the process of revision and is not available for sale. It will be available once again on August 4 and who knows, if the price is right I just might have to give it a try (although honestly, it looks kind of dorky).

I will leave you with some photos that we took on our trip to Sweden. Click on the photos to enlarge or view slideshow-style. Look carefully and you’ll see the Stierngranat coat of arms (with its exploding grenade) on several of the photos.

For further reading (some are in Swedish):

- A remarkable man and his life

- Baron Malte

- Stjärneborg Museum website – slide show has another view of the coat arms with grenade

- Malte’s Pyramid at Stjärneborg

- Stjärneborg Castle – just recently converted to a Bed & Breakfast property

- History of Nobynäs – from Nobynäs website

I also have copies of 10 newspaper articles from the 1899 jail incident – too long to post here. Contact me if you want copies.

UPDATES 4/7/2016 – Malte’s walking stick has been found!

Loved it, Karen. Did you find a way to translate the book you bought in Sweden? A flamboyant life. But he is not a relative – too bad!!

I used Google Translate for select bits and pieces from the book. There’s much of the book that remains untranslated. Maybe there are more tales yet to be told!