After reading and transcribing the Mexican War pension file for my great-great-great-grandfather Benjamin Black, I can now go back and write a biography for him that’s quite a bit more detailed than what anyone could have written before. But it’s probably not the legacy he would have wanted.

(Note: this is the second of two posts today that wrap up my research on Benjamin’s pension file. Part 1 is here.)

I was so excited to get the pension file once I found him on the index list back in February. I know next to nothing about the Mexican-American War and I was looking forward to learning about it through the lens of my ancestor’s experiences. I still don’t know much about that conflict, but the genealogical revelations have been pretty amazing!

My great-grandmother Lola Timmons wrote about her mother-in-law’s family and noted that Benjamin Black was one of nine children born to Samuel Black and his wife Elinor. According to Lola, one of the other siblings was Catherine, ten years older than Benjamin. Testimony included in the pension file confirmed that our Benjamin did indeed have an older sister named Catherine.

Lola thought that Benjamin was born in Boone County, but in his pension application, Benjamin said he was born in Madison County, which is quite a distance south. In fact, we find that there was an “Elenor” Howard married to a Samuel Black in 1812 in Madison County – so Benjamin may have been truthful about his place of birth. The marriage record shows that Elenor’s father was named Benjamin Howard which makes this all the more promising (and Benjamin named one of his daughters Elinor as well). The Howard family has a long and distinguished pedigree with plenty of documentation.

Samuel’s origins, however, are still murky. Lola thought that Samuel, Benjamin’s father, was born “perhaps” in Carlton, Virginia. I haven’t found a Carlton in Virginia, but in the course my research, I did find a Carlton Post Office in Boone County, Kentucky. Today, that little village is known as “Rabbit Hash” (famous for electing dogs as mayors, read the Wikipedia article, it’s funny). We now know that Samuel had a sister (Benjamin’s aunt) who was Cynthia’s grandmother – suggesting that the Black family was firmly ensconced in Kentucky for at least a generation or two before Benjamin’s birth.

There are several “Samuel Blacks” in published genealogies on ancestry.com. One Samuel Black emigrated from Ireland, and another was descended from a long line of Ulster-Scot Blacks who founded the town of Blacksburg, Virginia. Many of them were Presbyterian ministers. Yet another Black family with five sons settled in Ohio, perhaps part of the Blacksburg clan, but the dates associated with that particular Black family don’t align well with Benjamin’s family. Lola mentioned this family in her notes; I don’t know where she got her information.

In any event, I am included to believe that our Benjamin Franklin Black was born to Samuel Black and Elinor/Elenor Howard in Madison County, Kentucky on May 14, 1823. This date is mentioned in the pension application and it matches Lola’s notes exactly. In about 1842, at age 19, he went to live with his sister Catherine and brother-in-law Henry Harrison Boggess, who may have been living in or near Indianapolis, Indiana.

Benjamin returned to Boone County and got caught up in the State’s enthusiastic response to a call for soldiers to serve in the Mexican War. In fact, the Governor of Kentucky eventually refused the service of 75 companies because there were so many more volunteers than were needed. Benjamin joined a local company and marched with his friends down to Louisville and trained with them for a couple of weeks. It’s hard to say what went wrong – he either got disillusioned, sick, or just found that military life wasn’t going to be a good fit. He and a buddy deserted their company and after they were discovered missing, they were burned in effigy. The angry response may have been prompted by the situation with the surplus of volunteers; I suspect that having a couple of deserters may well have threatened the company’s eligibility to deploy to service in Mexico.

Benjamin’s desertion was apparently reported in the newspapers and known in the community, so he left Kentucky a second time. I believe it’s most likely that he reconnected with the Boggess family in Indiana once again. According to census records, the Boggess family was living in Shelby County, Indiana by 1850. Henry Harrison Boggess would later be elected as a Sheriff of Shelby County and he served as a soldier in the Civil War.

Benjamin was married to his first wife Louisa Mathews in Shelby County in 1849. It seems that Louisa was from a respected family and her father was a sometimes-minister and charismatic leader. Benjamin seemed to have a history of being surrounded by larger-than-life male figures – his brother-in-law Harrison Boggess, his father-in-law T.Q. Mathews, and perhaps even his own father if the stories about ministers are true. Benjamin the deserter had to know, deep-down, that he did not live up to the standards of these strong, respected men in his family.

In 1850, Benjamin and Louisa were living in Shelby County with their newborn son Samuel. Benjamin’s occupation is listed as blacksmith. By the 1860 census, the family has grown to include six children, but their places of birth reveal a rather nomadic existence, with children born in three different counties over the 10-year span between the censuses. In 1864, my great-great-grandmother would be born in yet another county in Indiana (DeKalb), and by 1866 the family had moved to Iowa County, Iowa where Louisa’s father had moved several years earlier. Louisa may have been ill with tuberculosis.

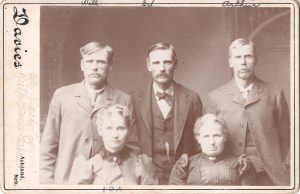

Front: Ida and Ruth

Shortly after their arrival in Iowa, Louisa and her newborn twins died, leaving Benjamin as a widower with eight children between the ages of 2 and 17. He was in over his head. The older children tried to help with the younger ones and no doubt did the best they could. Neighbors Edwin and Isabel Rosecrans stepped in to raise the youngest, Ida, and eventually adopted her as their own. Although Benjamin doesn’t seem to have been a very good father, I don’t think he was abusive; maybe incapable would be a better word. His children seemed to have found stability as adults and maintained family ties between themselves (five of them posed for a picture at a studio in Ashland, Nebraska; maybe they were all together on the occasion of Ida’s wedding in 1886). Perhaps they benefited from their mother Louisa as the moral center of the family, compensating for Benjamin’s weaknesses.

Benjamin remarried to Sarah Coles, a widow herself with six children of her own. Benjamin and Sarah had two more children together, sons John and Berton Earnest “Earnie”. During his marriage to Sarah, we see that Benjamin tried to salvage his reputation. He is listed in the records of the North English Christian Church, where he chairs a finance meeting. He also officiated at the wedding of the church’s minister, John Gilchrist. Gilchrist was a widower himself, and when he remarried he doubtless recruited a trusted person in the congregation to officiate. Gilchrist’s grandson, John Dirom Gilchrist, would later marry Benjamin’s daughter Elinor “Ellen”1.

But eventually, his marriage to Sarah falls apart. Benjamin’s failings as a father had to be evident as his children scattered away. He may not have been much of a provider either, if his nomadic history in Indiana is any indication. By the time of the 1880 census, Benjamin is living as a boarder with the Brown family and his children from his first marriage are scattered and gone, many of them having moved to Saunders County where the Rosecrans family settled. Sarah and their two kids are living separately several miles away. We know from the pension file that he later boarded with a W.H. Smith in Keokuk County. The marriage to Sarah must have ended badly. By the time Benjamin wrote his will, he didn’t know the address of his youngest son, to whom he left a few meager possessions. Cynthia never even knew Sarah’s name.

In January 1887, Congress passes a law awarding service pensions to veterans of the Mexican War. Somehow, Benjamin finds out about this opportunity and concocts a plan to claim a pension benefit. He doesn’t waste much time. His application is submitted on May 3, 1887. The man he knew as Randal Corbin was dead and buried in Boone County, Kentucky. Benjamin knew this, and assumed Corbin’s identity. I wonder, who did Benjamin talk to in the spring of 1887? Who coached him on the finer points of filing a fraudulent claim? He doesn’t strike me as having the kind of gumption it would have taken to figure this out on his own.

His plan is almost tripped up because he can’t find anyone to vouch for him. After claiming that he hadn’t had contact with any of this fellow soldiers, he finally convinces one of Corbin’s follow soldiers, John Bills, to sign an affidavit on his behalf. John Bills was a shifty old pensioner living on a shanty boat on the Ohio River who couldn’t even sign his own name. How did Benjamin track him down? So many unanswered questions about Benjamin’s scheme…

The careless pension office awarded the pension to Benjamin in spite of Bills’ dubious affidavit. The law gave pension benefits to veteran soldiers over the age of 62. Benjamin was 64 at the time of the Act, so once his pension was approved he probably got a lump sum payment for all accrued benefits. I figure it may have been more than $200.

The careless pension office awarded the pension to Benjamin in spite of Bills’ dubious affidavit. The law gave pension benefits to veteran soldiers over the age of 62. Benjamin was 64 at the time of the Act, so once his pension was approved he probably got a lump sum payment for all accrued benefits. I figure it may have been more than $200.

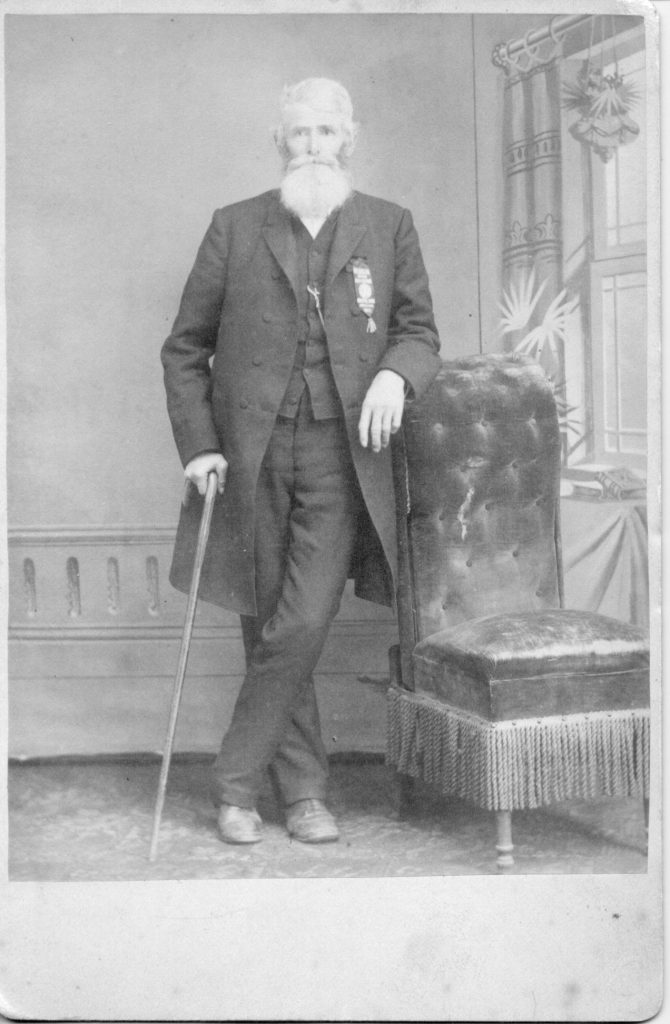

I think the first thing he did was to buy himself a new suit, pin a ribbon on his chest, and pose for a picture that he sent to his children. He was anxious to live up to the reputations enjoyed by his father, his father-in-law T.Q. Mathews, his brother-in-law Harrison and his good friend John Gilchrist. If his children had been ashamed of him before, maybe they wouldn’t be now.

I confirmed that this picture really is Benjamin! I found the original in a file, and Lola wrote on the back, “mother’s father Ben F. Black”. (Sadly, there is no photographer imprint on the picture for further confirmation.)

With his Iowa reputation tarnished, he took his fistful of cash back to his childhood home in Kentucky and soon found the welcoming arms and farm of a spinster cousin, Cynthia Jones, who admired him as a handsome, fine man. His health was in decline. Less than two years after their marriage, he died from what Lola reported as lung and kidney problems.

The Pension office failed to act on Cynthia’s application for widow’s benefits, even though the Special Examiner had recommended rejection. She and her attorneys must have taken this as a hopeful sign and kept at it for over 10 years until the official notice finally came in 1904. Cynthia probably struggled to make ends meet and had to take in a boarder to keep the farm afloat.

I have found no record of either his or Cynthia’s burial. As with Benjamin’s alter ego Randolph Corbin, they may have been buried on the farm rather than in a cemetery.

Word of his remarriage and eventual death reached his children somehow. But if they ever got word of his pension scam and Cynthia’s struggles, it remained a family secret until now.

So thus ends the story of my bona fide “Black” sheep ancestor! I’ve alternated between amusement and sadness. It’s odd to think that my very existence depends on Benjamin’s bad choices in life – had Ida not been adopted by the Rosecrans’ and moved to Saunders County, she would never have met and married my great-grandfather Edward Frasier.

1This information from Dennis Nicklaus, a Mathews descendant.

<–Part 8: The Final Report and Aftermath

A fascinating biography. I remember great grandmother Ida at her house in Havelock.

Hi,

I want to let you know that your blog is listed in today’s Genealogy Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2017/05/janas-genealogy-fab-finds-for-may-5-2017.html

Have a great weekend!