I hadn’t intended on making this a two-parter but I got some new information this week.

While doing some random Googling on this subject, I came across a book called “St. Joseph: Preserving a Heritage” by Idelia Loso that appeared to be about the German Catholic community in Stearns County. An online index of names listed in the book included a “Herman Krifles”, which sounded somewhat promising. I borrowed a copy of the book through interlibrary loan. It arrived yesterday and it turns out this is an excellent resource for our family! Here’s what I learned:

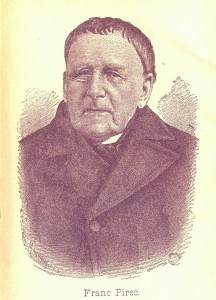

The first German settlers arrived in the St. Joseph area in 1854. A missionary priest, Fr. Pierz, came to the settlement from time to time to say Mass. Fr. Pierz is actually quite famous in Minnesota, and you can read more about him in this Wikipedia article.

He had a friendly relationship with the local Indians and helped them improve their farming. He observed that the Indians were being pushed out and he wanted to make sure that new settlers in the area were friendly to the Indians. So he published a series of letters in late 1854 and early 1855 in newspapers such the Wahrheitsfreund, which had a national circulation. The articles “described the beauty of the land and its healthful climate…he urged German Catholic farmers to come and take advantage of the cheap land,” according to Loso.

I have no doubt that Mathias Blommer and his two sons-in-law, Sebastian and Herman Kreifels, were motivated to make their move from Missouri after reading one or more of these articles. As I’ve noted previously, Mathias mentions “health” more than once in his letters as a reason for leaving Missouri.

In the summer of 1855, about 50 families arrived in St. Joseph township, the Blommer and Kreifels families among them. These were true pioneers! They had to clear the land of trees and break the soil – hard, hard work! Mosquitoes were terrible during the summer, and the winter of 1856-1857 was extraordinarily difficult.

Adding insult to injury, a plague of locusts in 1856 wiped out the entire harvest. When the nymphs hatched the following spring, they ate up the new crops that were just sprouting, effectively killing the crop. Having eaten everything to the ground, the locusts swarmed and left the county in June of 1857.

They had money problems, too. The first settlers were basically squatters since there was not yet a procedure for deeding out the land. In 1860 a public notice stated that they had 60 days to come up with the money to buy their land or else it would be sold at public auction. Some had to scramble to get loans, and unscrupulous lenders were charging upwards of 36% interest. Others just kept their fingers crossed, hoping that there would be no buyers. Some of them were able to wait until the passage of the Homestead Act to get title to their land. Based on the land record indices and Mathias’ writings in the last post, it seems as though Mathias and Sebastian may have coughed up the dough while Herman may have waited it out. Still much research to be done to confirm all of this.

In 1858, the Township of St. Joseph was officially organized and one of its first tasks was to set about getting the road system built. Herman Kreifels was appointed as one of the “overseers of the roads” and was elected as constable. They organized six road districts and required each able-bodied voter to contribute two days’ work each year to the roads. A visitor to the area in 1872 made the following report:

St. Joe is noteworthy for the industry, harmony, honesty, and consequently the prosperity of its settlers, who are mostly all German. With bridges and roads among the best in the State, it is wholly out of debt, and generally winds up its year’s accounts by having a balance in the treasury that its ‘wise men’ do not well know what to do with; for they have not yet learned at St. Joe to steal themselves rich…I have visited no rural settlement where industry seems to be better systematized than in St. Joe.

Good job, Herman!

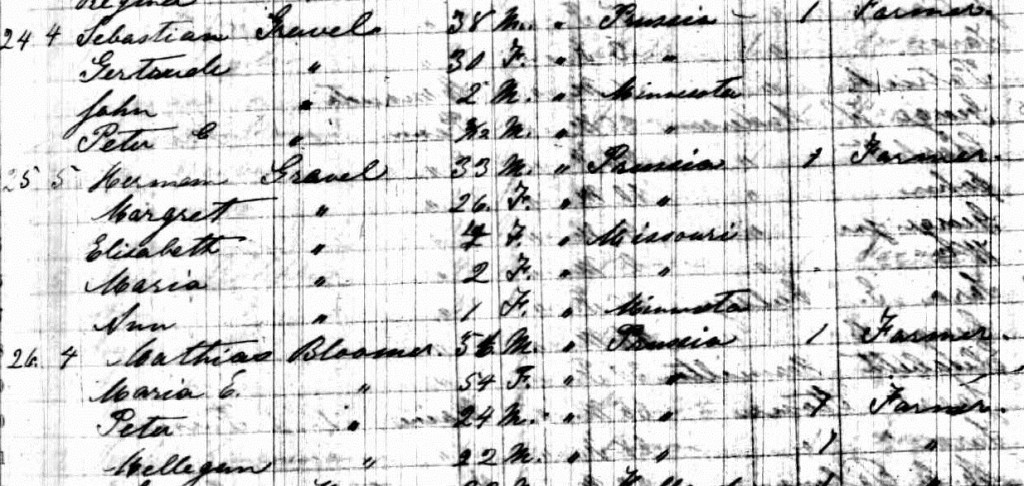

The State of Minnesota took some state censuses during this period. Here is a record from September, 1857 showing Sebastian, Herman and Mathias all living on adjacent farms. (Note the continued difficulty with spelling! This time, “Kreifels” is spelled as “Gravel.”)

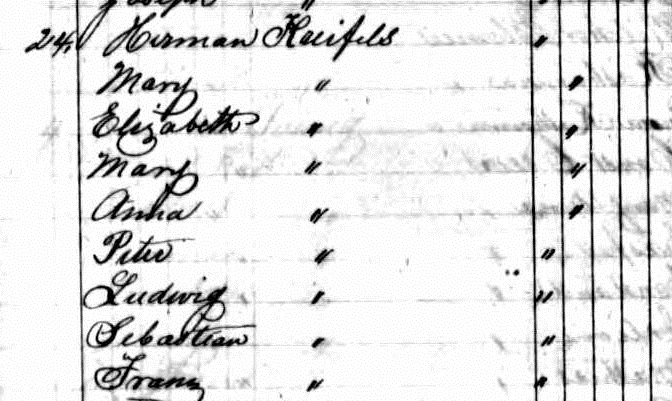

Here they are again in 1865, this time living further apart from one another and listed on separate pages in the census. First the entry for Herman Kreifels. Here we see Ludwig listed – he would have been about five years old. Later in life, he would be known as Louis Kreifels and was Elizabeth (Kreifels) Rademacher’s father.

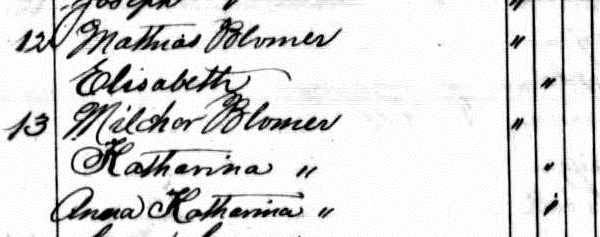

Next is the entry for Mathias. He and Elisabeth are now empty-nesters but are living next door to their son Melchior and his family:

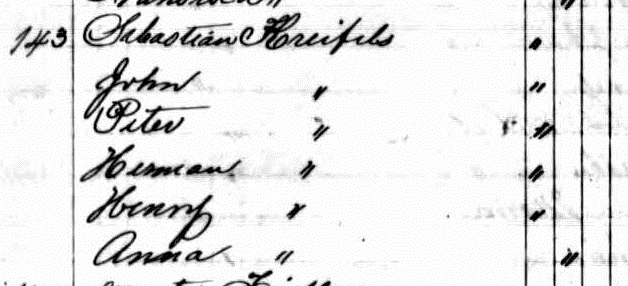

And here is Sebastian. His wife had died the year prior, so he is now a single dad with five young children:

It looks to me like the census-taker was a German – the gothic influence in his script is unmistakeable.

As I noted previously, the winter of 1868-1869 was another dreadful one, prompting Herman and Sebastian to formulate plans to move to Kansas – but they ended up in Nebraska. How did that happen? That’s where we’ll pick up the story next time.