Among the “assets” included in Daniel Dill’s estate were three enslaved persons: Nancy, Sam and John. The administrator, E.B Gould, had to manage them along with Daniel’s other personal property, real estate, and cash. It’s an eye-opening look at one small aspect of slavery in the South.

I want to state right away that I feel ill-equipped to understand and write about Daniel’s slaves. Much of the probate file is concerned with disputes about how the slaves were managed after Daniel’s death. And it pains me to even write the phrase “how the slaves were managed” in a sentence. Nancy, Sam and John were real people who deserve some measure of dignity 150 years later. Even referring to them as “slaves” seems so de-humanizing. Please know that my intent is to write about them as respectfully as I possibly can.

After Gould was appointed as Administrator1 on June 30, 1855 [ref 1007]. His general task as administrator was to round up all of Daniel’s assets and make sure they were equally distributed to his heirs. For all practical purposes, that meant he would need to sell everything and distribute the cash proceeds. So his first task was to take Bolin Smith’s inventory and get an appraisal of all the assets that were listed. He got right on it, and by July 5 the appraisers had completed their report [ref 1001]. They determined that Daniel’s brick townhouse and adjacent lot were worth $6,500. He had some cash and investments worth about $350 and a whole bunch of personal possessions that added together were worth around $180. He had two rent payments coming due for the music store tenants in his house, and $62 left to be received on a loan made to his brother Andrew Dill.

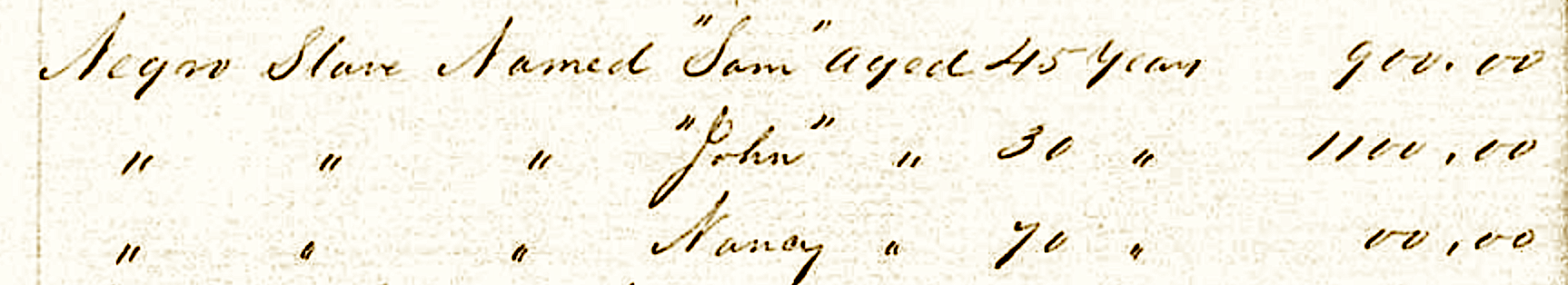

And then Daniel also owned the following [ref 1002]:

The inventory lists three “negro slaves”. Sam was 45 years old and estimated to be wroth $900. John was 30 years old and was valued at $1,100. Nancy, age 70, had no monetary value at all.

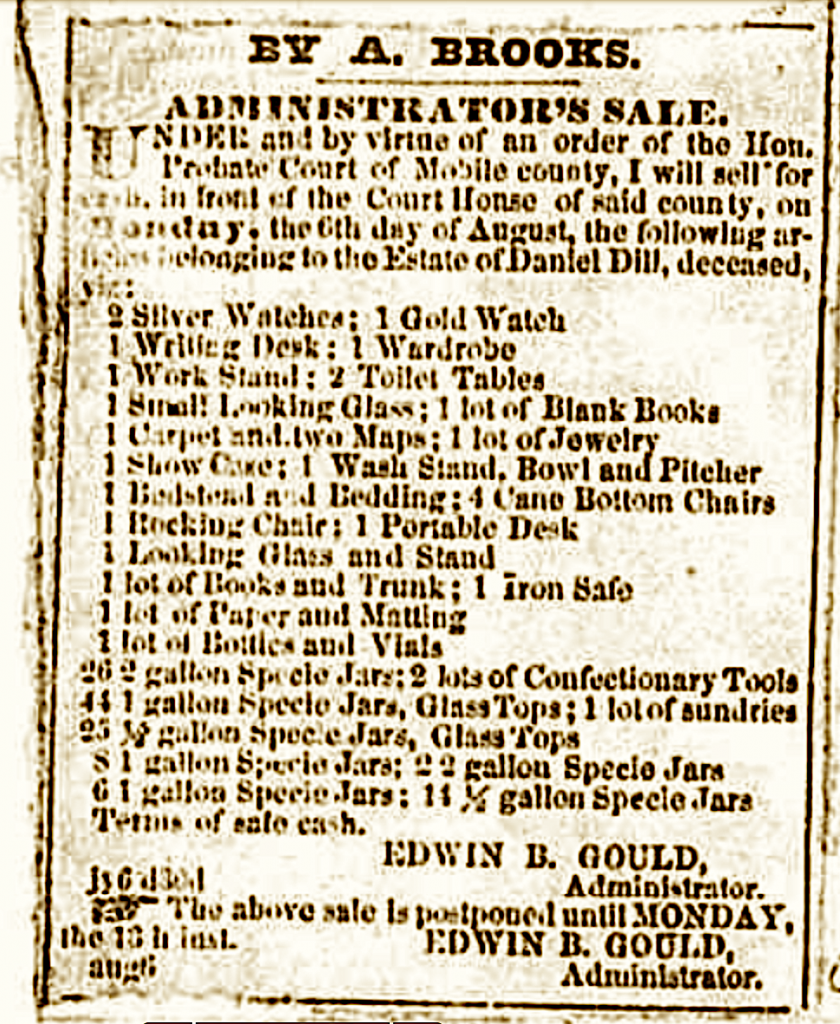

Gould immediately arranged for an auction of all the personal property. The probate file includes a newspaper clipping of the advertisement of the sale [ref 1016]:

The appraisers had it about right as the auction brought in about $185 [ref 1017].

He was unable to sell the real estate because it was tied up in the lawsuit against the Chastang family.

Gould probably couldn’t sell the slaves right away either. During the last few years of his life when Daniel wasn’t running a business any more, it seems that he put his slaves out for hire. John was working in Lauderdale Springs, Mississippi at the time of Daniel’s death [ref 1002]. Sam may have been working for James Shotwell’s grocery store. (Nancy may have been able to do some light housekeeping for Daniel but the file isn’t very clear about that.) Until their hiring contracts were complete, Gould probably couldn’t sell them.

For some reason, however, Gould made a trip to Lauderdale Springs to recover John. As I mentioned last time, I’m not sure why John was in Lauderdale Springs or who he was working for.

Gould submitted a receipt and itinerary for his trip in a later accounting to the probate court [ref 1029] .

He traveled by rail and by stage coach and incurred hotel and food expenses. Some sort of legal proceeding was involved as he incurred expenses for 2 days board in Enterprise (Mississippi) “waiting for case Sunday morning.”

As John’s and Sam’s hiring contracts expired, however, Gould probably would have done right by the estate (financially) to sell them. Instead, he continued to hire them out. The heirs would later accuse Gould of doing this for his own benefit – skimming money from the rent payments and underreporting the income.

When slaves were hired out, the owners were apparently still responsible for clothing and medicine. The probate file is full of receipts for the meager clothing purchases made on their behalf. These are among the most heartbreaking documents in the file. It’s clear that some of the clothing for Sam and John was intended to make them presentable for jobs such as waiters or cooks.

But I wonder, was this level of spending perhaps more than what Daniel had been providing before he died? Were Gould and his fellow merchants generous in provisioning the slaves in order to make an extra buck or two? I guess even if their motives were less than pure, we ought to be glad in hindsight that extra clothing may have been provided .

Gould was even more generous with the provision of medicines. No doubt it was because he procured all the treatments from his own drugstore! The itemized receipts are full of pills, “bitters”, laudanum and pain killers. I guess if the treatments were medically necessary it was nice that they were provided. But one also wonders whether slaves were being medicated into submission? Or given unnecessary and possibly dangerous medications to line Gould’s own pockets?

Somewhere along the way, someone got suspicious of Gould. I think it was Daniel’s former clerk, Lewis Ayers. Lewis would have known a great deal about Daniel’s business affairs and possibly about Daniel’s family.

Eventually, Daniel’s younger brother Peter – my 4x-great-grandfather – got word of what was going on down in Mobile. Next time we’ll find out how Peter intervened.

I’ve scanned several of the receipts and documents related to Sam, John and Nancy and included them in the gallery below. Included are a work permit for Sam, and a receipt for bailing John out of jail. Most of the receipts are for clothing and shoes. Click on any one of the images to see them enlarged.

It’s sad to think that the receipts in Daniel’s probate file are the only real evidence that John, Sam and Nancy even existed.

1All references to the probate file are image numbers from Ancestry’s online version. See Original Will Records, Daniel Dill, Pigeon Hole No 85, Files 9-41, 1814-1946, Index, 1813-1957; Author: Alabama. Orphans’ Court (Mobile County); Probate Place: Mobile, Alabama.