Daniel Dill’s probate file and the State and Federal census records can be combined to paint a vivid picture of Daniel Dill’s life in Mobile, Alabama. A candy store, a fancy house and more…

The 1840 census lists only the head of the household by name, with tally marks for other members of the household. The members of the household are classified into various categories. Daniel’s household is described as having three white persons: Daniel himself, plus two others who are presumably “clerks” (according to later censuses) – one in his twenties and another in his early teens. There are also four slaves. Three of them are named in his probate file. They are Nancy (in her fifties?), Sam (about 30) and John (late teens). There is another younger male slave (under age 10) who we do not see in later censuses or documents. Two members of the household are employed in “manufacture and trade”. I assume these to be Sam and John who help Daniel in his business (more about that in a moment). One person is employed in “commerce” – this is likely Daniel himself as a business owner1.

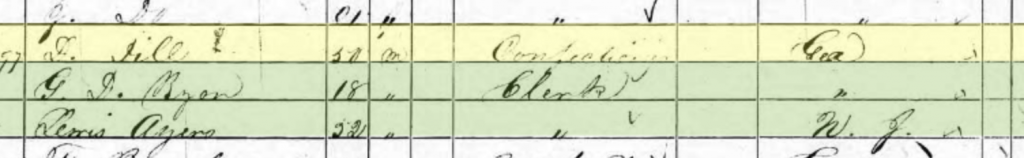

The 1850 census provides more detail on the household2. We learn that Daniel’s occupation is “confectioner” and we confirm that he was born in Georgia in 1800. The other members of his household are G.D. Ryan, an 18-year-old clerk, and Lewis Ayers, a 53-year-old clerk. Whether these are the same members of the household from 10 years prior is not known. Ryan is also from Georgia – lending credence to the idea that Daniel spent some of his adult years there after leaving Ohio. Lewis Ayers will feature prominently in our story later on – he is from New Jersey.

In the 1850 census, the slaves are listed on a separate schedule. They are identified by age, gender and skin color: a “mulatto” male, age 30; a black male age 20; and a black female age 603. We know their names from the probate file; they are Sam, John and Nancy.

What does it mean to be a “confectioner” in the mid-19th century? I believe it means he is a candy maker, of all things. We see further evidence of this in his estate inventory. We’ll talk more about his estate in future posts, but the inventory showed that he owned dozens and dozens of “species jars” which were probably used for display.

He also owned “confectioners coppers”, which were probably kettles and utensils used for heating and caramelizing sugar. I found a set from 1840 listed in an auction in London. It went for £4,375 (over $5,600 ) earlier this year! In Daniel’s inventory, it was appraised at $15.

I wonder how in the world he found his way into the candy business?

I believe his candy store was in his house, and that brings up another fascinating aspect of this whole story.

The inventory shows that Daniel owned a house at 40 Dauphin Street in Mobile, Alabama. Dauphin Street still exists today, and it goes right through the heart of downtown Mobile.

The inventory specifically locates the house on Dauphin Street between Royal and Waters. All of these street names still exist, so we can pinpoint on a map exactly where Daniel lived.

Dauphin Street was a fancy neighborhood in Mobile at the time, and Daniel’s property had a colorful history. It had once been owned by Dr. John Chastang (1738-1813), who had received it as part of a large land grant from the Spanish government in 1756.

John fell in love with his brother’s slave woman, Louison, so her purchased her and freed her. They had 10 children together. The Chastangs were Creole – that is, persons of mixed French and African ancestry. They were and continue to be a large and well-respected family in Mobile. To this day, there are schools and streets in Mobile named after the Chastang family. You can read more about John and his family on their family history website.

After John died, the property apparently sat idle, and the City of Mobile platted it out and made lots available for development. I’m not clear whether Daniel’s house was actually built by Chastang or if some later landowner constructed it. It changed hands several times before Daniel bought it.

Over the years, the Chastang family tried and failed to get their land returned. At first it was John’s son Bazile leading the effort, filing suits perhaps a couple of times in the years before Daniel owned the property. Bazile has a fascinating history, too. He successfully petitioned the Alabama Legislature to free a family of slaves that he owned – they were actually his wife and children. When Bazile died, his heirs continued the efforts to get the land returned.

The heirs of John Chastang and Bazile Chastang wouldn’t give up. At some point, they brought suit against Daniel to recover the house and land.

According to the probate file, Daniel’s attorney assured him that their suit was, like the previous ones, completely without merit. However, this legal matter would be a sticky problem for Daniel’s estate for years longer than anyone could have anticipated.

Daniel had a circle of friends and neighbors in Mobile that become important in our story. We’ll meet them next time.

Sources:

1“Ancestry.Com – 1840 United States Federal Census.”Census Place: Mobile City, Mobile, Alabama; Roll: 10; Page: 101; Family History Library Film: 0002334

2“Ancestry.Com – 1850 United States Federal Census.” Census Place: Mobile, Mobile, Alabama; Roll: M432_11; Page: 377A; Image: 208

3“Ancestry.Com – 1850 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules.” Census Place: Mobile City, Mobile, Alabama; Image 43 of 81.