Finding a 368-page probate file for an ancestor you didn’t know much about is HUGE. A big file usually means the probate was contested. It was surely bad news for the family at the time, but great news for the genealogist looking at the file 160 years later!

It seems wise to take a step back and consider what I have learned and where to go from here. Here are my take-aways from Daniel Dill’s probate file.

- What to make of Daniel Dill? So now that it’s all said and done, what do I make of Daniel Dill? The probate file gives us a lot of facts but not much insight into his character. I think he was smart, entrepreneurial, and hard-working. He must have been affable and outgoing in order to keep customers returning to his successful confectionary store. But his moral fibre is more than a little suspect considering his slaveholding and the apparent acrimony between him and his late wife’s family.

- What do make of Edwin Gould? Gould was eventually tossed out as the estate administrator and ordered to pay back funds that weren’t properly accounted for. He had a history of bankruptcy and tax avoidance. I do think he cozied up to Daniel in the hope of getting some sort of windfall upon Daniel’s death. The evidence showed that he mismanaged the estate – the house was in foreclosure at one point due to non-payment of taxes. He apparently paid back the estate with what I think he knew to be worthless Confederate paper. But I also think that Daniel took advantage of the Gould family during his illness. He should not have expected to receive their attentions without offering compensation, and he had the means to do so.

- Quaker Ancestry Many Dill researchers have shown that Phebe Brown (Daniel’s mother) had Quaker heritage. I’ve seen enough in my research of Daniel to be convinced that it’s true, and I believe there is a lengthy and detailed trail of documentation going all the way back to the British Isles. Can’t wait to get started on this!

- New insights into the Dill family origins. Future research on the Dill family should focus in the Lincoln County and Columbia County region of Georgia. These are adjoining counties. The two brothers, Daniel and Peter, have solid ties to this area. Lincoln County is where Daniel’s father-in-law (also a Dill) had his will probated, and Columbia County is where Peter’s father-in-law (Mercer Brown) had his will probated.

- Slavery is in my family history. Having watched practically every episode of “Who Do You Think You Are?” and “Finding Your Roots“, I’ve come to realize that most white Americans with colonial roots can expect to find that the institution of slavery has intersected with their family history in some way. What’s interesting in this instance is that Daniel’s maternal grandfather, Mercer Brown, was an ardent Quaker pacifist and even spoke out against slavery. We find the following in the 1788 Monthly Meeting records of the Quaker community in Wrightsboro, Georgia1:

The Preparative Meeting mentions to this meeting that William Hoge holds a Negroe in Slavery therefore this meeting appoints John Stubbs and Mercer Brown to visit and treat with him endeavouring to convince him of the iniquity of such practice and make report to a future meeting of their care therein.

I guess we learn from this that the Quaker community was not united in their opposition against slavery. Mercer was recruited to speak to a fellow Quaker – a member of his own community – about slaveholding. I guess we can’t be too surprised, therefore, that Mercer’s grandson Daniel ended up a slaveowner.

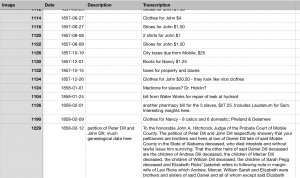

- Read and process every single page of a probate file. To fully understand Daniel’s probate file, I made a spreadsheet with a line item for every single page of the probate file. The spreadsheet has four columns:

Image number – this corresponds to the image number on Ancestry so I can always cross-reference to the original image when needed.

Date – most probate files, whether paper or digital, do not have their contents in chronological order. Whenever possible, I entered the date that the particular page was actually created and if it wasn’t explicitly stated, I estimated as best as I could. This means I can then sort on this column to get the file in chronological order.

Description – I didn’t always put anything in this column but if the particular image was a cover page or the back side of a document without any relevant information, I would put something like “cover page” in this field so I could filter those entries from view.

Transcription – any page that wasn’t a cover page, I tried to transcribe as best as I could. I didn’t bother trying to capture any formatting, I tried to keep it as much like “raw” plain text as I could. This makes the spreadsheet easily searchable, and also allows me to copy-paste the text information into this blog or other locations. Transcribing old handwritten documents in really difficult but worth the effort. I am sure that I spent more than 15 hours transcribing the file.

Once I had the file fully transcribed, I screened out the cover pages and then sorted in chronological order. That made it really easy to understand how the probate process unfolded.

I recently watched a webinar about probate files that was enormously helpful and I wish it had been offered sooner. It was called “Beyond the Docket Books: Digging for Gold in Probate Packets” and was offered by Legacy Family Tree webinars. I learned that many of the loose pages in the probate file are duplicated in docket books if you know where to look. Usually the court clerks had better handwriting than the lawyers of this era, so the docket books and journals are good places to look if you’re unclear about the spelling of key names and places.

- Follow every lead, even the trivial ones, and make connections. For example, when I learned that Daniel Dill and his slave Sam traveled on a ship called Champion, I wanted to know more about the ship itself – what kind of ship was it? Who owned it? It was fascinating to learn that the ship had been built by Cornelius Vanderbilt.

- Question all previous assumptions. Lots of people have posted trees on Ancestry that show that Daniel died in 1843. I don’t know who first made this assumption, but it has been copy-pasted all over the place, and never with any form of supporting documentation. I can’t stress how important it is to use online family trees as a source for CLUES but never ever as a source for FACTS. Even if someone cites a source on Ancestry, verify it for yourself.

Now that I’ve wrapped up the “Curious Case of Daniel Dill”, I’m looking forward to moving on to some new subjects. I have new news on the Fraser family and plans for exploring more about the Martinson family. Stay tuned!

Love it!