The Civil War halted all progress on settling Daniel Dill’s estate and, of course, changed the life course of everyone connected with Daniel Dill and his assets.

At the time the war broke out, Lewis Ayers was the administrator of the estate. He had been Daniel’s trusted clerk for many years – it’s possible that Lewis had even been with Daniel back in Georgia. I believe that Lewis tipped off Daniel’s extended family about the alleged mismanagement of the estate; Daniel’s brother Peter was all too eager to endorse Lewis as a replacement for the discredited Edwin Gould.

Lewis got the accounts in order, rescued Daniel’s house from foreclosure, sold the slaves, and continued to lease out Daniel’s property to the music store tenants. In March, 1860 – Lewis gave his first annual report to Judge Hitchcock1. He was still waiting to get control of Daniel’s cash assets [ref 1246]:

…no part of the funds of in the hands of the former administrator have as yet come to his hands decreed by your Honor as his final settlement to be paid over to your petitioner but … will be eventually paid he has no doubt.

Lewis also told the judge had not been able to make any further progress in tracking down heirs to the estate.

On April 4, 1860, he submitted a receipt for court expenses [ref 1254] and then the file goes dark. The Civil War started a year later on April 4, 1861. It appears that the normal affairs of the probate court in Mobile, Alabama ground to a halt. Mobile itself was the scene of intense fighting, including the Battle of Mobile Bay. It was in this battle that Commander Farragut uttered his famous words, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”2

Let’s explore the impacts to the major players in this story. Some of the information we glean from the post-Civil War documents in the probate file, other information comes from census records and other sources.

Edwin Gould finally repaid his debt to the estate – with Confederate dollars! [ref 1288] It’s unclear at what point during the war he made the payment. At one point, the value of the Confederate dollar was only 6 cents relative to the United States dollar. This happy circumstance for Gould stood in contrast to a subsequent tragedy. His second son, Emile, was killed in the waning days of the war and was buried in Magnolia Cemetery in Mobile. Emile’s gravestone reads3:

In memory of

E. STRADER GOULD

son of E.B. and M. Gould

he belonged to

Co. K, 21st Ala. Reg. and was

killed at Spanish Fort

April 1st, 1865

aged 20 years

Silvester Festorazzi, Daniel’s former competitor and the new owner of Daniel’s slave Sam, became something of a Confederate hero in Mobile. He served in the same regiment as Gould’s son:

In 1861, Silvester Festorazzi, a native of Italy, organized the Southern Star Guards, a company of Italians and Spaniards, and became their commander. This company was attached to the 21st Alabama regiment and served with distinction. Nearly all available Italian and Spanish residents of the city had gone into the company at the outset.

After the conflict Captain Festorazzi received a pardon in the Name of President Andrew Johnson. It begins like this: “Whereas Silvester Festorazzi, of Mobile, Alabama, by taking part in the late rebellion against the government of the United States, has made himself liable to heavy pains and penalties…”4

Frederic Hartel, Daniel’s tenant, seems to have abandoned Mobile during the course of the war. He was not listed in the 1866 city directory, but we do find him in 1870 taking up his profession as a piano maker and piano tuner in New Orleans, Louisiana5.

Frederick Bromberg, Daniel’s next door neighbor, stuck it out through the war and in 1866 is still running a “music and variety” store in Mobile with his sons.

The Dill Family By 1870, Daniel had only three of his seven siblings still living: Peter (my 4x-great-grandfather) of Morgan County, Indiana; John (who had traveled with Peter to Mobile in 1858 to protest the handling of the estate) of Madison County, Iowa; and Elizabeth Rickes of Henry County, Indiana. I wonder if Daniel had any nephews who served in the Civil War? Something for future follow-up.

Jasper Strong had purchased Daniel’s slave Nancy and likely brought her to Pensacola, Florida where he had been constructing military facilities for the United States prior to the war. When war broke out, he probably found himself in a tricky situation. Although Florida was the the third state to secede from the Union, the United States retained control of Fort Pickens in Pensacola through the duration of the war. Strong, despite being a West Point graduate, apparently had no stomach for participating in the war on either side. He left Florida shortly after the war started, returning to his home state of Vermont where died shortly after the war ended. I don’t know what became of the 100+ slaves that he owned.

So what about Daniel’s slaves? I have not found anything definitive about their fate. I don’t even know for sure that, if they did survive the war years, whether they retained “Dill” as their surname.

The Emancipation Proclamation, signed on January 1, 1863, freed the slaves of the south but its true effects on the black population of the country are nuanced.

One major political effect that the Emancipation Proclamation had was the fact that it invited slaves to serve in the Union Army. Such an action was a brilliant strategic choice. The decision to pass a law that told all slaves from the South that they were free and encouraging them to take up arms to join in the fight against their former masters was the brilliant tactical maneuver. Ultimately with those permissions, many freed slaves joined the Northern Army, drastically increasing their manpower. The North by the end of the war had over 200,000 African-Americans fighting for them.6

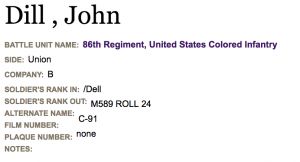

Southern port cities with a Union presence were obvious points of enlistment for former slaves. The National Park Service’s “Soldiers and Sailors” database contains an intriguing entry7.

Further digging shows that the 86th Regiment of the Colored Infantry served in Pensacola. Is this Daniel’s John Dill? Did he travel to Pensacola to find his mother? Did he enlist as a Union soldier?

Further digging shows that the 86th Regiment of the Colored Infantry served in Pensacola. Is this Daniel’s John Dill? Did he travel to Pensacola to find his mother? Did he enlist as a Union soldier?

I believe the records for this John Dill will show him to be about 10 years too young to be the same John Dill that was Daniel’s slave (still confirming this). But I believe age records for slaves to be highly suspect. Honestly, though, I don’t suppose we can ever know for sure whether this John Dill is the same person or not. I have to admit that it’s a bit of stretch.

For the white people of Mobile, a return to “normal” after the war was next to impossible. The City’s financial foundation was shaken without the slave work force it once enjoyed. Tax records for Daniel’s estate show a brief increase in property values immediately after the war, followed by a sharp decline.

Daniel’s estate had another problem, however.

Lewis Ayers, the estate administrator, died in September 1866 [ref 1290]. The duty to settle the estate now fell to Daniel’s former neighbor, Frederick Bromberg. He would be the fourth and final administrator of the estate.

Next time we finally find out how the estate was settled.

1All references to the probate file are image numbers from Ancestry’s online version. See Original Will Records, Daniel Dill, Pigeon Hole No 85, Files 9-41, 1814-1946, Index, 1813-1957; Author: Alabama. Orphans’ Court (Mobile County); Probate Place: Mobile, Alabama.

2https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Mobile_Bay

3https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=87372273

4http://modmobilian.com/2010/07/mod-mobilan-history-festorazzis-coffee-saloon-i/

5https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/70252845/person/40214986213/facts

6http://historycooperative.org/effects-emancipation-proclamation/