I have been super-busy at work and have not been able to keep up with genealogy as much as I would like! In this post about P.W. Pearson’s probate records, we’ll look at the paperwork filed with the court in March, 1921: the Judgment on Claims.

By March of 1921, it had been nine months since Will’s passing. The family had somehow kept the farm going through 1920, harvesting crops and managing their livestock. Farm prices were falling terribly, but they somehow managed to keep food on the table. I imagine that Clara probably had worrisome meetings with her attorney and many sleepless nights.

To let all potential creditors know that P.W. Pearson’s estate was to be settled, the law required that notices be put in four consecutive editions of the local newspaper (in Clara’s case, the Wahoo Wasp). Anyone who thought they were owed money could petition to the court to have their bills included.

The estate Inventory filed just a month earlier showed that the farm equipment and animals were worth about $2,200. Debt in the form of three promissory notes came to a total of $2,700. The 160-acre farm itself is listed as an asset, but its value was not shown. Its value was somewhat of an illusion anyway, since it was mortgaged to the tune of $8000 and had annual interest payments of $440 due on it. At first glance, this doesn’t look too terrible. She could sell everything things she owns to pay off debts and then scrape together another $500 to pay off the rest. She’d keep the farm, but – here’s the kicker – she would have none of the livestock or equipment necessary to make a go of it. Realistically, she’d have to allow the farm to go into foreclosure. She’d walk away debt-free, but she would at that point be completely destitute with no place to live, no job, and no money. So really, this isn’t a viable option at all. Let’s call this “Plan A”.

Her lawyer had already filed a paper with the court back in October 1920 to have the will thrown out so that the estate could be administered by statute. Doing this would allow her to claim certain portions of Will’s estate ahead of the creditors. The law allowed her to claim all of Will’s “wearing apparel, ornaments and household furniture” and $200 worth of his personal property. Another provision of the law allowed her to claim “one cow, three hogs, all pigs under six months old, one yoke of oxen or a pair of horses” plus other necessities, such as three months of food for the livestock, a living allowance, and certain farm implements.

So here’s “Plan B”: Clara takes all the cash and property to which she is entitled, then sells the rest to pay off the the creditors. In fact, it appears that her attorney is setting things up for Plan B – it might have been a good plan had the economy not gone bad. But since she doesn’t have enough to fully pay the estate’s creditors, the farm is probably at risk. In theory, the creditors might want to go after the mortgage holder (Widow Putney of Wahoo), force a sale, and fight over who gets what. Meanwhile, Clara has the remnants of a farming operation but no farm, and the estate stiffs a lot of her friends and neighbors in the community. Who would want to rent land to her meager little farming operation after such an ordeal? And keep in mind that while people file for bankruptcy all the time these days, it carried much more of a stigma 100 years ago. In the end, Plan B really isn’t much different than Plan A. She just gets to keep a bit more cash and personal property away from the creditors.

The only other option on the table is what I will call “Plan C”. Plan C means borrowing enough money from someone to pay off all the claims against the estate. She’ll be able to keep the farm (although it’s still mortgaged) and will hope to be able to operate it well enough to raise four kids. The problem is, she has absolutely no collateral. Her farm is already mortgaged. What bank or person would want to loan a widow that kind of money in the middle of a farm crisis?

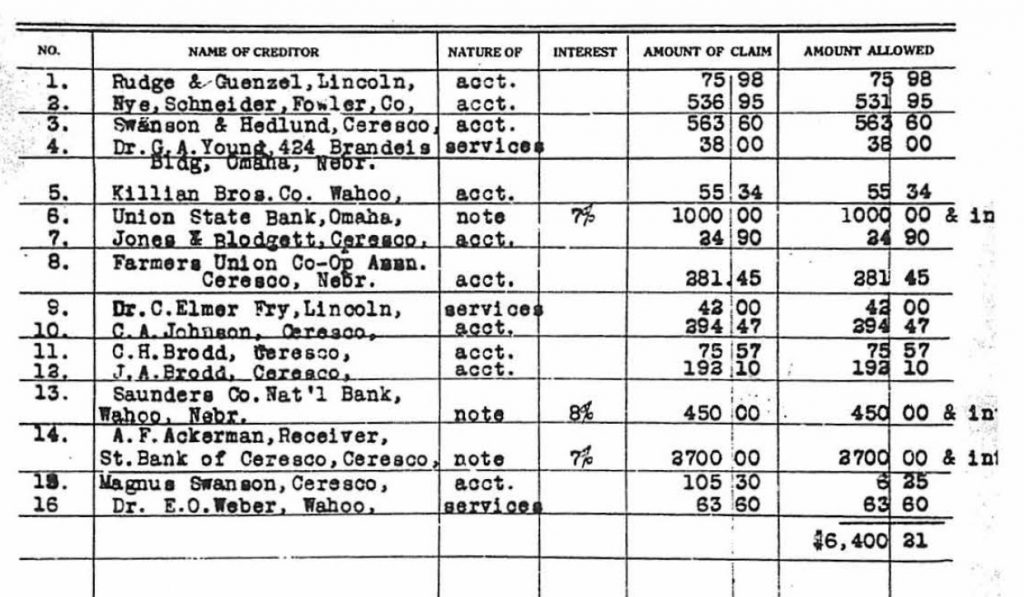

So let’s look at the Judgment on Claims and see just how bad the debt is.

Okay, it’s bad. It’s really really bad.

Based on the inventory, we expected to see debts of at least $2,700, plus the amounts owed on some of the bills owed to various lumber and implement dealers that had accumulated since Will died.

What the inventory didn’t show was two more promissory notes – one to the Bank of Omaha for $1,000 and another to a bank in Wahoo for $450. And then lots of smaller bills to doctors and family members. It all added up to an astounding $6,400.

Someone will need to come through for Clara and make Plan C work out somehow. We’ll find out who next time.