Wow, I hate it when real life gets in the way of genealogy! Don’t know when “regular programming” will resume, but I wanted to at least get this last part of the Swedish probate document up on the website.

To review: Johannes Månsson was the grandfather of Gust Rudeen (my great-grandfather). Johannes was the first of my Rudeen ancestors to live on the Eket farm in Marbäck parish. He passed the farm on to his son, Peter Anders Johansson, and retired with his wife to a nearby backstuga (a rustic cottage). At age 62 he died from typhoid fever. As required by Swedish law, an inventory of his estate was prepared. These estate inventories are just one of the many wonderful records available to modern-day researchers with Swedish ancestry.

I should mention here how these estate inventories were conducted. Typically, the surviving spouse and heirs would request the inventory. At an appointed time, court appraisers would come to the home and conduct the inventory in the presence of the family. Family members would sign off on the inventory to indicate their agreement. Later, the court would determine how the assets would be distributed. Typically, the surviving spouse would get half of the estate. The children would divide up the remainder, with sons getting twice what the daughters received.

In Part 1 we reviewed the preamble portion of the inventory, which listed his survivors and heirs. In Part 2 we reviewed the detailed list of his possessions. In this final part, we will look at the list of his fordringar (amounts owed to the deceased) and his skulder (debts owed by the deceased).

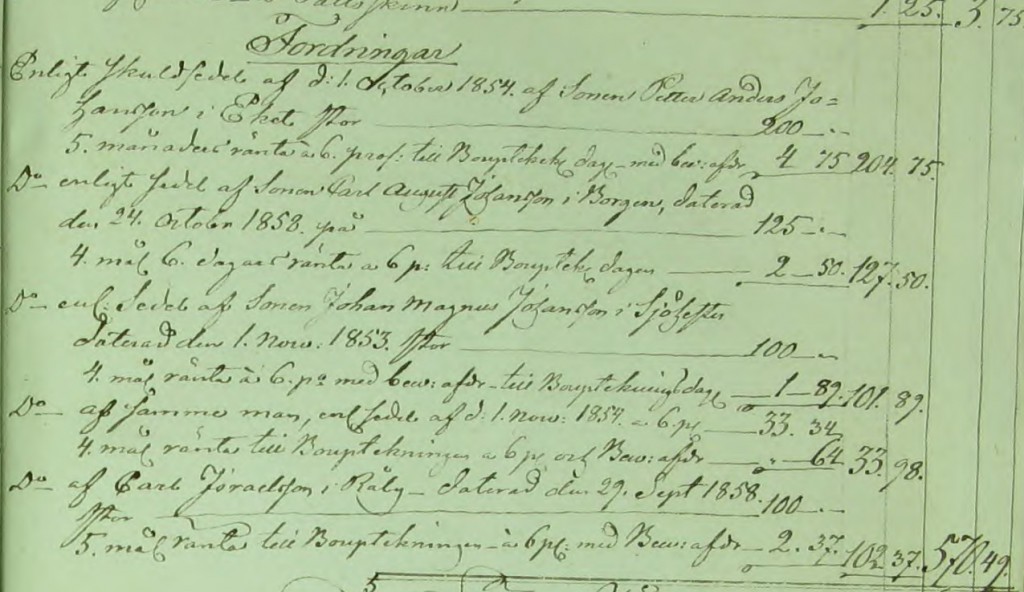

Johannes had several loans outstanding at the time of his death. In total, he was owed 570.49 riksdaler. The value of all his possessions was only 114.85, so he had let out quite a bit of his net worth in the form of loans to family and friends. Here’s the list:

| Owed From | Subtotal | Total |

| Under the promissory note of 1 October 1854 of son Peter Anders Johansson of Eket | 200 | |

| + 5 months interest | 4.75 | |

| Total | 204.75 | |

| Under the promissory note of 24 October 1858 of son Carl August Johansson of Borgen | 125 | |

| + 4 months interest | 2.50 | |

| Total | 127.50 | |

| Under the promissory note of 1 November 1853 of son Johan Magnus Johansson of Sjöhester | 100 | |

| + 4 months interest | 1.89 | |

| Total | 101.89 | |

| Under the promissory note of 1 November 1854 to the same man (Johan Magnus) | 33.34 | |

| + 4 months interest | 0.64 | |

| Total | 33.98 | |

| Under the promissory note of 29 September 1858 to Carl Israelsson of Råby | 100 | |

| + 5 months interest | 2.37 | |

| Total | 102.37 | |

| Grand Total | 570.49 |

To summarize, he had made loans to all three of his sons: Anders Peter (Gust’s father and the tenant of Eket), Carl August (who would be the first to come to America nine years later, also the first to take the name Rudeen), and Johan Magnus. He had also made a loan to a Carl Israelsson who may be a tenant or perhaps a son-in-law (more work to do on this family, for sure!).

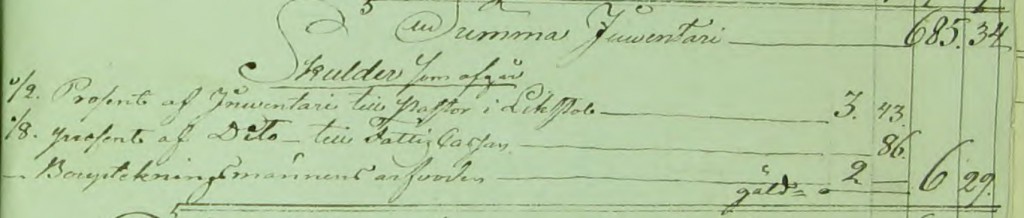

As far as debts go, he had hardly any. It appeared that he owed some fees related to the preparation of the inventory, plus a poor tax of 0.86 riksdaler.

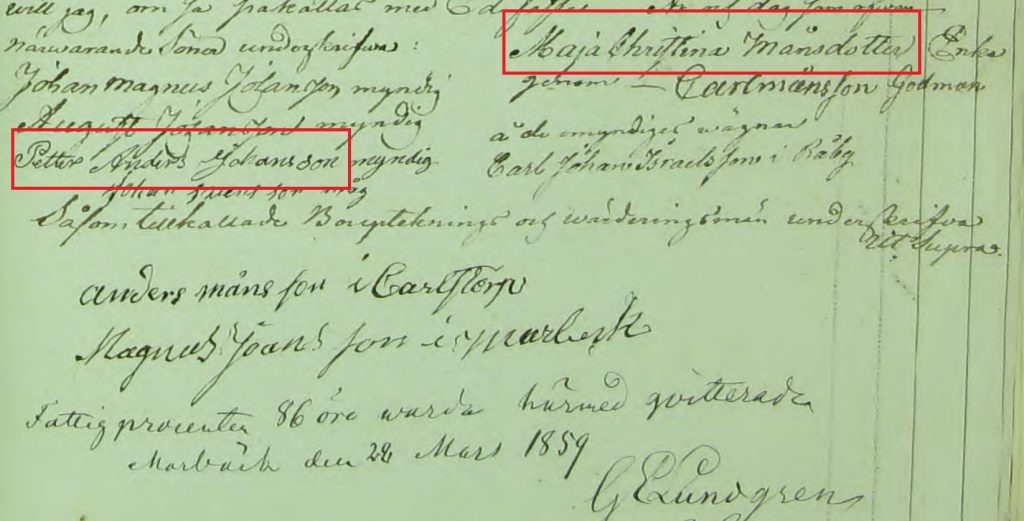

My favorite part of the document is the bottom portion, which shows signatures. Here we can see the signature of my great-great-great-grandmother Maja Christina Månsdotter (the widow) and that of my great-great-grandfather Peter Anders Johansson (one of the heirs).

A few reflections:

It seems as though Johannes Månsson did quite well for himself! He was able to acquire enough assets over time to give each of his sons a good start. His household inventory suggests that he was living comfortably although he had little in the way of valuables.

I was surprised to see evidence of formal promissory notes! Making formal loans to family members requires a pretty high degree of financial literacy, it seems to me. Papers need to be drawn up, interest rates need to be agreed to, and books need to be kept. I had no idea that this type of transaction was going on in rural Sweden in the mid-1800’s! Did they use a bank? Where? The nearby modern town of Aneby didn’t even exist until the 1920’s.

It also seems that most if not all of the family was literate. The signatures appear to be authentic, and the inventory shows that Johannes himself also owned a Bible and some books.

It seems that the Eket farm provided very well for Johannes during his lifetime.

A Rudeen Probate in Sweden – Part 1

A Rudeen Probate in Sweden – Part 2